March Employment in Rhode Island: How Worlds Diverge, by Justin Katz

Economy

8:30 AM, 04/20/13

Notebook Entry: "Secretary of Commerce vs. RICWFA paradox", by Carroll Andrew Morse

Basic Government Functions

9:15 AM, 04/ 5/13

Minimum Wage Workers and the Threat of Increases, by Justin Katz

Economy

2:50 PM, 04/ 3/13

The Three Ts Are Proving to Be About Ruling Class Insulation, by Justin Katz

Economy

9:02 AM, 03/21/13

Rhode Island Changed Last-Place Unemployment Partners in January, by Justin Katz

Economy

10:07 AM, 03/20/13

A Revision in Time Saves 1600, by Justin Katz

Economy

8:57 AM, 03/11/13

02/20/13 - Economic Development Presentation, State House, by Justin Katz

Economy

1:50 PM, 02/20/13

Things We Read Today (46), Weekend, by Justin Katz

Political Thought

7:57 AM, 01/14/13

Concluding a Strange Season for Employment Data, by Justin Katz

Economy

1:43 PM, 01/ 4/13

November Employment: Rhode Island's Peculiar Growth Abates, by Justin Katz

Rhode Island Economy

7:39 AM, 12/27/12

April 20, 2013

March Employment in Rhode Island: How Worlds Diverge

Watching the employment statistics, as presented by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) from month to month, offers an interesting perspective on how people can develop different understandings of objective reality.

Tracing the unemployment rate, one might think Rhode Island is undergoing a strong recovery. In January 2010, it was 11.9%, and for years the state was among the worst three, periodically claiming the lead spot. This past March, though, the rate was 9.1%, which puts five other states in a worse position.

But viewing the statistics in terms of employment, not unemployment, changes the picture entirely.

April 5, 2013

Notebook Entry: "Secretary of Commerce vs. RICWFA paradox"

A brief exposition of an entry put down in an actual dead-tree notebook, referring to a news-subject worth watching, at a time where there is certainly no shortage of subjects vying for public attention...

Secretary of Commerce vs. RICWFA paradox -- A group of Rhode Island leaders led by General Treasurer Gina Raimondo announced a plan in late March to help Rhode Island municipalities secure low-interest loans for infrastructure projects through the quasi-public Rhode Island Clean Water Finance Agency. At about the same time, the Rhode Island Public Expenditures Council pitched to the House Finance Committee its plan to move a chunk of the the quasi-public Economic Development Corporation's function to a Secretary of Commerce position situated inside of the Governor's office. This seems, at least on the surface, to have things a bit backwards, with a quasi-public organization assuming a significant role in providing a public good, i.e. maintenance of roads and bridges, while the government-proper devotes more energies to "economic development", most of which ultimately must happen outside of government.

According to WPRI.com's Ted Nesi, "the treasurer's office estimated communities could save $1 million on every $10 million in loans thanks to the lower rates they'd get by borrowing through the AAA-rated [RICWFA]", but the ability of a city or town to pay off debt doesn't change because it takes a new route to get a loan, and adding a new middleman isn't a guaranteed method for lowering the cost of something. It is fair to ask if there's a more fundamental issue with RI cities and towns paying more than they need to for lending, if someone else will be assuming risk of default in RICWFA routed loans, or if there's some other cost to this plan that's not immediately obvious.

(Bumped upwards, from an original April 4 posting date)

April 3, 2013

Minimum Wage Workers and the Threat of Increases

A quick update study from the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity finds that legislative proposals at the state level to increase the minimum wage to $8.25 per hour would cost workers in the state 432 jobs, measured against last year's $7.40 per hour rate.

Even worse would be the proposal suggested by U.S. Congressmen Jim Langevin and David Cicilline to increase the national minimum to $10.10. That would cost 3,466 Rhode Islanders their jobs.

In a press conference this morning, replayed in large part by Dan Yorke on 630 WPRO, the Congressmen presented the image of struggling families working full time in minimum wage jobs just to subsist. That is simply not the profile of this group of people.

March 21, 2013

The Three Ts Are Proving to Be About Ruling Class Insulation

What are Governor Lincoln Chafee's three Ts of economic development, again? Is it talent, technocrats, and tolerance? Or is it technology, tolerance, and twee ideological fashion? It can be so difficult to keep these gimmicky strategies straight.

This particular strategy is also turning out to be difficult to make work. In fact, it may just be a description of a handful of cities that chance made "hip," rather than a workable, replicable strategy for turning around any given city. Indeed — as should probably be expected when we give broad authority to powerful people to plan the society in which everybody will live — it appears that pursuing a "creative class" strategy tends to produce the sorts of communities that serve powerful people and the cool folks with whom they like to hang out.

March 20, 2013

Rhode Island Changed Last-Place Unemployment Partners in January

The message making the rounds on Rhode Island's January employment numbers is that it represented a slight, if mixed, improvement, because the unemployment rate fell to 9.8%, the lowest it's been since early 2009. A large reason for that fact, however, is that a methodological revision by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics made more people disappear from the Rhode Island labor force than it did from the employment rolls.

Now, the January numbers show another large drop in the labor force, nearly 1,400 people, thus "improving" the unemployment rate, even though actual employment fell for the first time since September 2011. The reason is that only 681 fewer people reported being employed. That's quite a different picture from Rhode Island's new partner in last place for unemployment, California. The latter has continued to add employment, but people entering and/or returning to the labor force have kept its unemployment rate from going down.

March 11, 2013

A Revision in Time Saves 1600

In George Orwell's 1984, the protagonist, Winston, begins to notice the import of the revisions that he makes to news and history as an employee of the Ministry of Truth. No fact is so set in stone that it can't be made to look better through revisions of the past.

In the real world, nationally, as well as locally here in Rhode Island, the newspapers have been touting the lower unemployment rates. Somehow the massive revision of the numbers and change of the methodology have gone sparsely mentioned.

February 20, 2013

02/20/13 - Economic Development Presentation, State House

Another economic development study presentation at the State House, liveblogged.

January 14, 2013

Things We Read Today (46), Weekend

Perspective from on high; the empathetic view from my soap box; cover-up as economic development; what happens when that which can't go on forever doesn't.

January 4, 2013

Concluding a Strange Season for Employment Data

An unanticipated (unprecedented) leap in employment just prior to this year's presidential election brought the Current Population Survey (CPS) data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) an unusually high degree of technical scrutiny. As I've been noting, the seasonally adjusted and unadjusted results have been a bit peculiar. With data from December now available, the BLS concluded the year by changing five years' worth of seasonal adjustments and announcing changes that will make subsequent years "not directly comparable" to anything that came before.

For the final month of the year, the "headline" unemployment number, which is the percentage of people in the labor force who say they are actively seeking work, held at 7.8%. Two frequently highlighted considerations are that, one, certain demographic groups are way above that percentage and, two, the rate would be significantly higher if the American labor force hadn't slowed its pace. If the labor force of the last five years had continued to grow at the rate of the prior five years, the unemployment rate would be 8.6%.

But it's the difference of seasonal adjustment that illustrates the peculiarity of this year.

December 27, 2012

November Employment: Rhode Island's Peculiar Growth Abates

After two months of unexpectedly strong employment growth, Rhode Island's surge abated. Unemployment held at 10.4%, leaving the state at second worst in the nation, with Nevada rapidly making up the distance, and the number 3 California finally slipping below 10%.

According to survey data released by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the pace at which increasing numbers of Rhode Islanders say that they are working fell to about a third of what it had been for September and October, to 1,501. Meanwhile the labor force increased by 1,411.

December 17, 2012

Things We Read Today (42), Weekend

The lesson of current events and history; what the 2nd Amendment means; what that means for change; government control and healthcare insecurity; government control and economic stagnation; a couple positive notes.

December 12, 2012

Things We Read Today (41), Wednesday

Two narratives on the economy; a health exchange story the media is missing; government as pretend leader; powerful teachers' unions (plus Ted Nesi's Rolodex)

State Comparisons: Right to Work and Beyond

A stunningly biased article by AP writer Jeff Karoub on the front page of today's Providence Journal likely captures the attitude of most in the Rhode Island media on the issue of right-to-work legislation, as enacted into law in Michigan, yesterday:

The GOP-dominated House ignored Democrats’ pleas to delay the final passage and instead approved two bills with the same ruthless efficiency that the Senate showed last week. One measure dealt with private-sector workers, the other with government employees. Republican Gov. Rick Snyder signed them both within hours, calling them “pro-worker and pro-Michigan.”

Yes, that plea-ignoring, ruthless GOP. Not mentioned in the article, in the paper, or in any mainstream RI media that I've seen was reportage of a unionist mob tearing down a large tent set up by Americans for Prosperity, while bystanders plead with them to stop because people were inside, and physically attacking a conservative commentator, after a Democrat legislator promised that "there will be blood."

The Projo's reporters are a unionized subset of the AFL-CIO, after all.

December 9, 2012

Things We Read Today (40), Weekend

What subsidizes green?; what the unions want the pension law to say; First Family Holiday Fame; America, the Special.

December 8, 2012

Mortgaging the Economy

Marc Comtois highlights another fascinating glimpse into the reasoning behind policy ideas that he and I agree are, well, in error. I'm speaking of this paragraph from Slate's Matthew Yglesias:

... I'm especially enthusiastic about the mortgage part. Suppose homeowners in expensive coastal cities couldn't deduct their mortgage interest, what would happen? Well, what would happen is that prices would fall. But nothing more dramatic than that. All the deduction does is encourage further bidding up of the price. In a normal market, that bidding up of the price might lead to additional construction. But the main reason those blue metro areas have such expensive houses is that zoning doesn't allow demand to be matched with supply. No matter how expensive Georgetown or Harvard Square or Park Avenue gets they're not demolishing the existing structures and replacing them with much larger ones. So you'd get some extra tax revenue this way with no real change in the amount of underlying economic activity.

Look, I've been known to make statements about the effects of policies that are arguably over-confident, but at this level of detail, human behavior has a definite x-factor of which policymakers (and policy-propounders) should beware.

December 7, 2012

The Philosophy of Noose Tightening

Providence Journal opinion columnist M.J. Anderson offers a fascinatingly candid look at the thought processes of those whose preference for expressing concern for people is through government programs, and at how it ultimately makes a cheap trinket of freedom.

The bulk of her column describes the terrible dynamic of ObamaCare that is leading employers to shift their emphasis toward part-time workers so as to avoid the choice that the federal government has given them: pay for expensive health plans or pay a penalty. ObamaCare sets a threshold of 50 employees working 30 hours or more per week before the mandate kicks in. As with minimum-wage laws, the rest is basic math and economic incentive.

Folks who share my philosophical view of the world look at this situation and see an argument against ObamaCare.

December 3, 2012

Open Thread: The Rhode Island Economic Development Corporation

Philip Marcelo of the Projo reported last week that...

Governor Chafee said on Friday that he is not considering major changes to the state Economic Development Corporation, despite a state-commissioned report calling for a major overhaul of the embattled agency, which came under fire for its handling of the 38 Studios debacle.I know every other state has some sort of economic development body (RIPEC provided a summary of them, at the end of its report on the RI EDC issued earlier this year), but what exactly is it that an "economic development agency" is supposed to achieve?

The question isn't whether government should be involved with economic development; one way or another it will be. As Justin pointed out earlier this year, during his Ocean State Current coverage of a non-profit/business community get-together, there is a strong perception from people who are trying to do economic stuff that the major way in which government is frequently involved in the current RI economy is as something that needs to be worked around. This leads to a first question: can an economic development agency make any difference with a government as broken as Rhode Island's is?

The other question is more fundamental: Even under as reasonable as can be hoped for conditions of good government, what exactly is it that a mission-specific economic development agency can do (whether as a quasi-public agency or as a regular government department) to bring about more improvement in the Rhode Island economy that directing the same level of "resources" (i.e., moolah) to more fundamental functions of government cannot?

Ted Nesi, in his Saturday morning post for WPRI-TV (CBS 12), recalled that the RI Department of Economic Development, the forerunner to the current Economic Development Corporation, was only created in 1974. The state got by without one for several centuries. Could it do so -- could it even be advantageous to do so -- again?

November 29, 2012

Things We Read Today (37), Thursday

Changing unions' privatization strategy; the government spending ratchet; the government spending racket; and the trap of dependency.

November 28, 2012

Things We Read Today (36), Wednesday

Threats to the economy (cliffs and debts); RI lagging again (yawn); dependors and dependees; Social Security a problem; and a civil right to the war zone frat party.

November 27, 2012

Things We Read Today (35), Tuesday

Healthcare and what you get for free; making a living trying to fix the dying (state); the dictator prescription; and unhealthily sexist (female) teachers.

The Unmentionable Solution to the Fiscal Cliff

Watch public policy even for a short while and the trick becomes evident. Whether we're talking my hometown of Tiverton, Rhode Island, (population 15,780) or the federal government, the maneuver is to claim increasing amounts of power and make sure that's the one thing not on the table when something has to give.

Thus, we get massive government interwoven like a terrible tumor around the vital organs of our economy. When the predictable illness follows, the two operations suggested, as if in opposition, are cuts on the spending side and increases on the revenue side.

Either, we're told, is apt to drive the patient into shock. The government can take money out of the economy through taxes, or it can stop putting money into the economy via cuts. That's not much of a choice.

November 26, 2012

Things We Read Today (34), Monday

Political theory (watching where you're going); bonds added to the pool of bubbles; safe regions in a pool with dangerous; government as the most dangerous bubble.

November 23, 2012

Free Market Argument for Copyright Reform

There was a bit of a controversy earlier this week when a policy brief from the Republican Study Committee was released advocating for major copyright reform with regards to intellectual property--and then it was "unreleased". The reasoning given was the the report was actually not properly vetted, whereas the belief amongst many was that lobbyists--such as the Motion Picture Association of America and the Recording Industry Association of America--got to the GOP.

As Lisa Shuchman reports, Rep. Darrell Issa, who was a strong opponent of SOPA, is regarded as someone with both the pull and desire to get something done on this front.

“The bad news for the movie studios and record companies is that the discussion about how to make copyright law make sense in a digital age has already started in Washington, and it will continue, with our without them,” Gigi Sohn, an attorney and president and co-founder of the public policy non-profit Public Knowledge, wrote in her blog.So, while it's not "official", here is the brief in full. And, to give you some flavor, here is the conclusion, which argues for reform based on free-market principles.:Indeed, Public Knowledge and others advocating for change to the copyright system have at least one ally in Congress. Rep. Darell Issa, who sits on the Judiciary Committee and its Intellectual Property, Competition and the Internet Subcommittee, wrote on his Twitter account Monday that the report was a “very interesting copyright reform proposal” and "It's time to start this copyright reform conversation."

The Congressman, who emerged as a leader on issues related to Internet rights earlier this year when he opposed the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), has already said he plans to make digital rights a priority in the new Congress.

To be clear, there is a legitimate purpose to copyright (and for that matter patents). Copyright ensures that there is sufficient incentive for content producers to develop content, but there is a steep cost to our unusually long copyright period that Congress has now created. Our Founding Fathers wrote the Constitution with explicit instructions on this matter for a limited copyright – not an indefinite monopoly. We must strike this careful Goldilocks-like balance for the consumer and other businesses versus the content producers.There is much more free-market based reasoning within the brief. As they say, read the whole thing (it's only 9 pages!).It is difficult to argue that the life of the author plus 70 years is an appropriate copyright term for this purpose – what possible new incentive was given to the content producer for content protection for a term of life plus 70 years vs. a term of life plus 50 years? Where we have reached a point of such diminishing returns we must be especially aware of the known and predictable impact upon the greater market that these policies have held, and we are left to wonder on the impact that we will never know until we restore a constitutional copyright system.

Current copyright law does not merely distort some markets – rather it destroys entire markets.

November 21, 2012

To Starve or Gorge the Beast?

"[W]e've got to reduce spending before we can reduce taxes. Well, if you've got a kid that's extravagant, you can lecture him all you want to about his extravagance. Or you can cut his allowance and achieve the same end much quicker. But Government has never reduced. Government does not tax to get the money it needs. Government always needs the money it gets." ~ Ronald Reagan

Hence was born the idea of "starve the beast," a conservative core belief if ever there was one. But is it true? As explained in a recent column by Andrew Ferguson, economist (and libertarian) William Niskanen didn't think so.

Beginning in 2002, Niskanen published a series of papers and op-eds about tax cuts and spending increases that turned conventional conservative wisdom on its head....If we wanted a smaller government, he said, we would have to raise taxes....Niskanen, looking over 25 years of budget data, noticed something about STB ["Starve The Beast" ~ ed.]: It didn’t work. In fact, attempts to starve the beast by tax cuts seemed to lead to increased federal spending.That last--the ability of government to write checks on credit--was overlooked by STB advocates.Niskanen looked at both spending and taxes as a percentage of GDP. On average, he found, if federal revenues declined by 1 percent, federal spending increased by 0.15 percent. When revenues rose, on the other hand, relative spending decreased. A further study in 2009 by another Cato economist, Michael New, came to the same conclusion after the gluttonous administration of George W. Bush. Under Bush and his mostly Republican Congress, new benefits like subsidized Medicare drugs and increased federal education spending followed on the heels of large tax cuts.

Niskanen’s explanation for the failure of STB was straightforward, a conjecture based on standard economics: When you cut the price of something, demand for it will increase. Lowering taxes without lowering benefits meant that taxpayers were getting the benefits at a discount. The government made up the true cost with borrowed dollars that future taxpayers would have to repay. There was a big difference, Niskanen said, between a kid on an allowance and the federal government: The government has a credit card with no debt limit. {emphasis added}

[E]arly advocates of STB had counted on something that never materialized. They had assumed that as the debt piled up to finance annual budget deficits caused by free-flowing benefits, public outrage would force politicians to restrain spending without raising taxes. Yet we’ve had the deficits and the borrowing, in amounts that would have left Friedman and Reagan agog; what’s been missing is the outrage.People aren't outraged because they don't feel the immediate pain of increasing government because the money for government expansion is either borrowed or paid for by increasingly fewer individuals. So around 50% of the population feels no pain (they don't pay income taxes) while a majority of the rest pays relatively minimal amounts. And a lot of that pain is left to future generations. This aligns with Niskanen's reasoning for why higher tax rates lead to lower spending:

“Demand by current voters for federal spending,” he explained, “declines with the amount of this spending that is financed by current taxes.” When you make them pay for government benefits out of their own pockets, in other words, voters will want fewer of them. The journalist Jonathan Rauch put Niskanen’s point more pithily: “Voters will not shrink Big Government until they feel the pinch of its true cost.”Yet, as I mentioned, not everyone shares the tax burden evenly in our progressive income tax system. So, perhaps a flat tax would prove or disprove Niskanen's theory, but it's doubtful that will happen any time soon.

Ferguson's article brought some critiques of Niskanen's ideas. Noah Glyn offers up another reason for why government spending decreases when tax revenue increases:

[It's] the business cycle. As the economy grows, people earn more so they pay more in taxes; conversely, when the economy enters a recession, government revenue plummets. During recessions, however, the public relies on increased government spending, in the form of Medicaid, food stamps, and other transfer payments. (This can go the other way, too: Some state and local governments have used economic growth to justify increasing promises to government employees’ pension plans, but those costs typically come much further down the line.)This is buttressed by Ramesh Ponnuru's important, technical point and "thought experiment":

Let’s say we still had the Clinton-era tax rates and a (smaller but still quite large) long-term debt problem. Wouldn’t we be debating an increase in tax rates to a higher level than we are now? That seems to me pretty likely. The baseline from which we’re negotiating would be higher, perceptions of what’s tolerable would be higher, expectations of tax rates would be higher. On the Niskanen theory there would be a countervailing effect: In the interim the tax cuts caused spending to be higher and thus moved the spending baseline higher. But Niskanen didn’t find that a dollar of tax cuts were associated with a dollar of spending increases; he found that a 1 percent reduction in revenue over GDP was associated with a 0.15 percent increase in spending over GDP. So the countervailing effect would be smaller.Jonah Goldberg adds:

I always liked Niskanen’s argument, even if I didn’t quite find it persuasive. One thing that always bugged me about it which, to my surprise, Ferguson doesn’t mention, is the implicit assumption that Americans behave like rational economic actors with regard to what they get from government....The American species of homo economicus has been paying hundreds of billions to get rid of poverty for decades, what do we have to show for it? Poverty rate in 1975: 26 percent. Poverty rate in 2010: 26 percent. What a great return on the investment. Federal spending on education? Ahem...For reasons, good and bad, voters don’t treat tax dollars the way they do their own dollars. They don’t demand quality. They don’t demand accountability. They don’t push for efficiency. Many people think the government should spend money as if it comes from someplace other than the wallets of citizens and that what we get for it should be graded on some spiritual, emotional, philanthropic or metaphysical curve. How we spend for X so often seems to matter more than how much X is actually delivered.Yet, as Patrick Brennan argues, re-stating Niskanen's implicit premise, the missing demand for government quality is because so many have so little stake in the game.

People might be a lot more likely to start caring about where their tax dollars go (whether the ends are efficient and whether the money comes back to them) when those taxes are really substantial, broad-based, and they actually have to pay them.Brennan also compares U.S. expectations for government services to that of Europeans:

If you live in a society where, as Jonah pointed out Arthur Brooks has argued, the state is considered the main conduit for meeting societal needs and caring for the poor and vulnerable, you’ll care more about how well government works and whether it can care competently for you, and that’s a cultural matter. But it’s also important to homo economicus, because Leviathan has taken most of his paycheck, and he now has to hope, and should ensure, that government will provide for society at large, the poor and vulnerable, and even him at times, and do so as efficiently and competently as possible.Regarding the last, many conservatives (well, at least me) believe that a smaller government is one that is easier to make workable!There are obviously other explanations for these differences: Charlie Cooke has lamented to me on many an occasion that in Britain, the conversation about almost all government policies ends up being debates over efficacy of programs, not whether the programs should exist in the first place. Leaving aside the financial constraints Britain and elsewhere are now experiencing, if you don’t have a constitution with enumerated federal powers, a truly conservative and independently minded political movement, etc., you’re going to spend more time on making government work, not on making it smaller, and that’s for other reasons than I’ve just proposed.*

==========================

* Brennan expounded on the point later in the post: "It’s difficult to assess my thesis inasmuch as big government and the cultures that give rise to it have other negative effects on efficiency, so it’s possible citizens subject to a huge government and a regressive tax code get a more efficient government than they would if they didn’t have higher expectations than free-riding Americans, but still not a very efficient one. It’s been suggested, in fact, that it’s highly efficient yet regressive taxation (like light capital taxation, competitive corporate-tax rates, consumption taxes, etc.) that’s allowed places such as France and Scandinavia to have functional economies despite the burdens of absurdly large governments; perhaps it’s also the relative efficiency and usefulness of their government spending programs, and not just their tax system, that’s allowed them to manage as well. Thus again, economic preferences force the hand of citizens and politicians in a completely government-dominated society but not in one like America."

November 19, 2012

Inefficiency in Economic Development: Money Looking for Makers

Readers of Philip Marcelo's article, in today's Providence Journal, about restoration of the historic-structure tax credit program in Rhode Island should see some warning signs indicative of a broader flaw in government economic development:

... the national recession and a 2008 moratorium on the tax-credit program brought such projects to a near halt.Dozens stalled or never got off the ground, leaving around $150 million in credits –– which can be redeemed to offset business and personal income taxes — still pending final approval. ...

Millions of dollars more in credits also could become available, if developers do not meet a May 2013 deadline to show some progress on their projects. (A project must be fully completed and its expenses reviewed before state officials approve issuing credits.)

November 2, 2012

Strange Days for Employment Data

Today's "employment situation" release from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) presents what might be termed a mixed-but-still-tepid picture best summarized with this quotation:

Employment growth has averaged 157,000 per month thus far in 2012, about the same as the average monthly gain of 153,000 in 2011.

That's not much of an improvement, and it's not nearly enough to speak of anything like a healthy growth rate.

But a reasonable analysis, teasing out as much election-season politics as it is possible to do, has to admit the peculiarity of the report.

October 29, 2012

During Hurricane Sandy, Rhode Island Vendors Should Watch Their Prices

With the declaration of emergency for Rhode Island, Hurricane Sandy becomes the first instance in which a new law, passed by the Rhode Island General Assembly and signed by the governor this spring, goes into effect. H7409 (also S2606) outlaws price gouging during an emergency. In the heat of the experience, the adrenaline of survival pushes the consequences of public policy even farther out of the public consciousness than its usual peripheral place. Still, as we hunker down — with school canceled and government offices closed well in advance of the looming weather — interest in the storm creates an opportunity for education and debate.

October 25, 2012

Forced Disclosure of Criminal Background: A Novel Explanation for Rhode Island's High Unemployment Rate

... proffered in today's Providence Journal by the challenger in the House District Four race.

Asked about his own solutions, [Mark] Binder linked Rhode Island’s high unemployment, in part, to the large number of people who can’t get work because they are required to disclose their criminal histories on job applications. Binder told his audience at Laurelmead that he heard this story often in talking to unemployed people in the Camp Street area of Providence and believes the state should make it “so these guys don’t have to check that box” on an employment application.

It could only be good for the government reform effort in the state to have a Democrat Speaker toppled. In this case, that would involve a victory by Mark Binder. That does not, however, obviate the necessity to ask the almost painfully obvious question here: how does Mr. Binder's theory explain the situation of the vast majority of the unemployed in the state who, you know, lack a criminal background?

October 22, 2012

An Unexplected Surge in Employment

The national political scene saw quite a stir, the first week of October, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported a huge jump in employment and corresponding drop in the unemployment rate. As I noted at the time, a large percentage of the increase was attributable to people who are involuntarily working part time, rather than full time.

More curious, though, is that August-to-September is not typically a time for large increases. The September-to-October month is the one that brings a boost in hiring. That fact is usually obscured by the seasonal adjustment by which the BLS smooths the month-to-month results in order to highlight actual trends, but the not-seasonally-adjusted chart at the above link tells the tale.

This factor appears to be in play in the state data, too, especially in Rhode Island. In nine of the last twelve years, employment has dropped in September, before seasonal adjustment. And September has never increased by the 5,229 people reported in this year's results.

October 18, 2012

Rhode Island Economy Booming! Or Not.

According to a press release from the RI Department of Labor and Training — the last to report this data before the election — Rhode Island's unemployment rate dropped to 10.5% in September, its lowest level since April 2009. The change was on the strength of the state's " largest monthly increase of employed RI residents since the Bureau of Labor Statistics implemented the current methodology in 1976."

Did it feel as if Rhode Island's economy took off at an historic rate, last month?

October 15, 2012

Deregulation Isn't the Problem; Bailouts Are

Travis Rowley takes on the talking point that the "Bush tax cuts" and the deregulatory impulse are what (say it with me) got us in this mess in the first place. The core of the argument goes to those government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that backed mortgages for lower-income families:

Whenever Democrats cite “the failed policies of the past” in order to refer to Republican promises to loosen up government guidelines placed on private enterprise, they are purposely confusing plans to deregulate the marketplace with the lack of oversight on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – government-sponsored agencies (GSEs) that prominent Democrats sought to protect from Republican reforms.As early as 2001 the Bush administration was warning that the size of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was a “potential problem” that could “cause strong repercussions in financial markets.” And Congressman Ron Paul (R) spoke of an existing real-estate bubble, and predicted that it “will burst, as all bubbles do.”

Put differently, it wasn't the deregulation that caused the problem; it was the promise of bailouts if things went wrong. As I've pointed out in various parts, Fannie and Freddie became an alternative to government debt for a safe investment at a time when the stock market was creating more prospective money than even existed in the gross domestic product (GDP). ...

October 13, 2012

Government Debt and the Danger of Historical Growth

In today's Saturday column,Ted Nesi voices reasoning that is only possible in a society that's become hubristicly accustomed to economic growth as an inevitability:

If bond investors are offering Rhode Island the lowest interest rates in its history, shouldn't the state be borrowing more money right now? Gina Raimondo has hinted she’s thinking that way, and there are plenty of infrastructure projects that need to be done soon. Some people are opposed to any and all state borrowing, and that's fine – but if you're someone who acknowledges Rhode Island taxpayers will be borrowing money at some point over, say, the coming decade, shouldn't as much of it be borrowed as possible now, while interest rates are at historic lows and 10% of the state's workers are idle?

This is akin to the approach of a college student who lives beyond his means on credit, expecting the sort of paycheck that he's been told to expect ...

October 12, 2012

Things We Read Today (25), Friday

Observing the VP debate from within; flight from a failing region; surprising beneficiaries of a government bailout; a fable.

October 5, 2012

Employment: October Surprise or October Miracle?

A lot of people who watch policy and politics relatively closely were very surprised, this morning, to hear that the unemployment rate had fallen to its lowest level during the Obama presidency — a level last seen in January 2009. As James Pethokoukis notes, of the seasonally adjusted 873,000 jump in employment from August to September, 582,000 were people who want to work full-time but had their hours cut or were unable to find full-time work, involuntary part time, as they're called.

Given the sheer size of the jump in employment, though, some cynical folks on the political right are finding it to be a bit suspicious. In their view, the move would be in keeping with the Obama administration's request to defense contractors not to notify employees before the election of possible layoffs and promise to cover the cost if they are sued for it.

Obama's Economic Claims Debunked

John Merline at Investor's Business Daily put together the below chart to help explain the economic myths being told by the President (read the whole thing).

October 2, 2012

Things We Read Today (22), Tuesday

Economic development options, from all-government to government-dominated; the heartless-to-caring axis in politics; Southern New Englanders' "independence"; solidarity between Romney and his garbage man; the media coup d'etat.

October 1, 2012

Feeling Good On Monday Morning

I think back to the old Southwest Airlines commercial (see it) advertising the all the great things about Philadelphia, including the cabbie proclaiming "Well there's a lot, a lot of culture here" and then all the other people in the commercial just proclaiming the greatness of the cheesesteak. Sometimes, I feel like people here in RI do the same when talking about why Rhode Island is a great state. We have the beaches, we have umm, Boston and New York are nearby. Oh, there's the restaurants, and of course we have Del's slushy lemonade. There you go, case closed, I've made my case for why Rhode Island is such a great place, why we're all here and why everyone else should consider coming here.

Just in case we needed the other view point in one concise web site, we now have that. The state's Republican Party launched RIRankedLast.com. Some of the things to enjoy with your morning Cheerios can include the state's rankings in various surveys like our dismal unemployment statistics, cost for education and a comparison to its effectiveness, our infamous business climate, and one for all the people who have sought fit to keep the Democrats in one-party rule for pretty much their whole lifetime: RI is the 7th worst state to retire in. How's that one grab you? You've been voting Democrat for the last 40-45 years or so, you're finally getting ready to retire and the fruit of your labor is non-existent. Abysmal. About the only thing you can do is start scouring the internet for your new home in the Carolinas or Florida, like everyone else. You helped create this environment and when it isn't working out for you, you flee, leaving it for the rest of us to try to clean up. It's like using the toilet and neglecting to flush.

Anyway, crude allusion aside, the web site has other information like links to all the recently convicted politicians we've been able to enjoy as well as lists of alternatives to consider next month.

It's sad that such a site is necessary and maybe even this isn't enough to get the message across to people but hopefully it'll at least get some people thinking about whether it really is true that "Yeah, the Assembly is a bunch of scumbags, but I like my guy. My guy is good!" We'll see in about another 37 days.

September 30, 2012

Things We Read Today (21), Weekend

Bob Plain's petit four of class warfare; CA's bid for more pension fund dollars; a martial metaphor for regionalization; a downturn for the never-recovered; Coulter v. View mention of RI.

September 27, 2012

RIPEC's EDC Report Another Indication of the Question Not Asked

Yesterday, the Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council (RIPEC), a venerable Rhode Island policy "voice and catalyst" founded in 1932, released a report analyzing the structure of the state's quasi-public Economic Development Corporation (EDC) and suggesting a reorganization. Governor Lincoln Chafee requested the report in May, following the scandalous collapse of 38 Studios, which had been the major basket in which the EDC had placed $75 million in bond-sale eggs.

Fortunately, Chafee Spokeswoman Christine Hunsinger confirms, for the Ocean State Current, that the state did not pay for the report. That's fortunate because — despite its 62 pages of text and 73 pages of organizational charts, definitions, and other appendices — the document does little to justify any particular new economic development structure and nothing to answer the more fundamental questions about the state's worst-in-the-nation employment situation.

September 23, 2012

Things We Read Today (17), Weekend

Returning RI to its natural state; RI as a playground for the rich; the gimmick of QE; the gimmick of digital records; killing coal/economy; when "Mostly False" means true.

September 21, 2012

Things We Read Today (16), Friday

The narrative of the candidates; death panels and pension boards; the endgame of government debt; an enemies list.

August Employment Data for Rhode Island and the Nation

Once again, the headline is that Rhode Island's unemployment rate fell another tenth of a percent, to 10.7%. And at least it's true, this month, that employment went up instead of down. (The past few drops in the unemployment rate were a result of people giving up their job searches, so they weren't counted in the statistics.)

But people continued to leave the state's labor force, and the employment increase wasn't exactly dramatic, giving the impression that our decline hasn't turned around, but has edged toward stagnation.

September 20, 2012

Things We Read Today (15), Thursday

Issuing bonds to harm the housing market; disavowing movies in Pakistan and tearing down banners in Cranston; the Constitution as ours to protect; the quick failure of QE3; and Catholic social teaching as the bridge for the conservative-libertarian divide.

September 19, 2012

Things We Read Today (14), Wednesday

Why freedom demands father-daughter dances; the U.S., less free; PolitiFact gets a Half Fair rating for its Doherty correction; and the mainstream media cashes in some of its few remaining credibility chips for the presidential incumbent.

September 18, 2012

Things We Read Today (13), Tuesday

Days off from retirement in Cranston; the conspiracy of low interest rates; sympathy with the Satanic Verses; the gas mandate; and the weaponized media.

September 17, 2012

Things We Read Today (12), Monday

Chafee shows his bond cards, Chicago exposes a metric discord, Rhode Island misses the skills-gap/business-cost lesson, QE3 misses the inflation nebula, and college majors miss the mark.

September 14, 2012

Things We Read Today (11), Friday

Being right about district 1 messaging; PolitiFact prepares for the election; what's a charter; being right about quantitative easing, First Amendment; and Bob Dylan says what he means.

September 13, 2012

Things We Read Today (10), Thursday

Madness overseas and at home, lunacy in the Fed, the disconcerting growth of government, and the performance art of public-sector negotiations.

September 11, 2012

Things We Read Today, 8

Today: September 11, global change, evolution, economics, 17th amendment, gold standard, and a boughten electorate... all to a purpose.

September 10, 2012

Things We Read Today, 7

Today it's debt and gambling, from bonds to pensions to entitlements, with consideration of regionalization, ObamaCare, and campaign finance.

September 7, 2012

I'll Ask Again: Better Off?

What is 4:1? The ratio of people who stopped looking for jobs as compared to those who found one in August.

– Nonfarm payrolls increased by only 96,000 in August, the Labor Department said, versus expectations of 125,000 jobs or more. The manufacturing sector, much touted by the president in his convention speech, lost 15,000 jobs.– Since the starts of the year, job growth has averaged 139,000 per month vs. an average monthly gain of 153,000 in 2011.

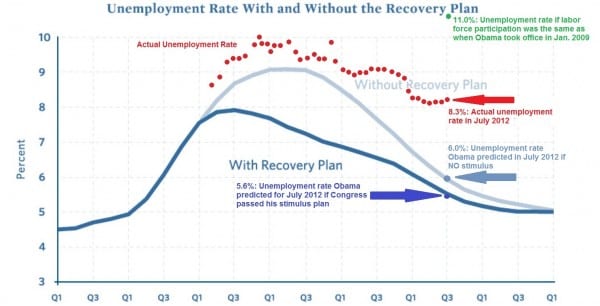

– As the chart at the top shows, the unemployment rate remains far above the rate predicted by Team Obama is Congress passed the stimulus. (This is the Romer-Bernstein chart.)

– While the unemployment rate dropped to 8.1% from 8.3% in July, it was due to a big drop in the labor force participation rate (the share of Americans with a job or looking for one). If fewer Americans hadn’t given up looking for work, the unemployment rate would have risen.

– Reuters notes that participation rate is now at its lowest level since September 1981.

– If the labor force participation rate was the same as when Obama took office in January 2009, the unemployment rate would be 11.2%.

– If the participation rate had just stayed the same as last month, the unemployment rate would be 8.4%.

– The Labor Department also said that 41,000 fewer jobs were created in June and July than previously reported. The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for June was revised from 64,000 to 45,000, and the change for July was revised from 163,000 to 141,000.

– The broader U-6 unemployment rate, which includes part-timer workers who want full-time work, is at 14.7%.

September 6, 2012

Things We Read Today, 4

Today, I touch briefly (for me) on long-term vs. short-term recovery, who's better off, RI's long spiral (and potential for quick resurgence), and the significance of different ballot types in Cicilline-Loughlin.

Government Surplus Wasn't the Problem; It's the How That Matters

In his daily flurry of tweets, WPRI reporter Ted Nesi linked to an interesting article by Joe Weisenthal in Business Insider. Weisenthal's conclusion is that the government surpluses of President Bill Clinton's second term were, themselves, the cause of the late '00s' economic bust:

The bottom line is that the signature achievement of the Clinton years (the surplus) turns out to have been a deep negative. For this drag on GDP was being counterbalanced by low household savings, high household debt, and the real revving up of the Fannie and Freddie debt boom that had a major hand in fueling the boom that ultimately led to the downfall of the economy. ...So while Clinton will be remembered nostalgically tonight, for both the performance of the economy and his government finances, they shouldn't be remembered fondly.

As if for authority, Weisenthal prints a PNG image of an economic formula (in a special formula font, even), but then he and his economist sources proceed to assert causation where there was only a temporary correlation in the parts of the equation during the Clinton era.

September 5, 2012

Things We Read Today, 3

Today's short takes address misleading labeling at the DNC, misleading fact-checking, fading national competitiveness, and the September 10 mentality.

September 3, 2012

Things We Read Today, 1

One thing I've learned, in years of blogging, is to be wary of proclaiming new regular features. Yet, I've been finding myself at the end of each day with a browserful of tabs of content on which I'm inclined to comment.

So, as interest and time allow, I'll publish quick-hit posts containing commentary that is somewhere between a tweet and a full-on blog post.

Leaning Against the Privileged Place of Investments

Readers shouldn't be surprised to hear that I'm largely in agreement with Peter Ferrara's "Obama's Accelerating Downward Spiral for America," but he happens to voice one bit of center-right common wisdom with which I have growing disagreement:

There is no secret or magic as to how to turn around these declining incomes. Increased investment in business expansion and start ups increases demand for labor, which drives up wages. That investment buys new tools and capital equipment for workers, making them more productive, which provides the cash flow to increase wages.Increasing investment results from reducing the tax rates on investment, which enables investors to keep a higher percentage of what they produce, increasing incentives for investment.

My resistance to this suggestion — notwithstanding Ferrara's positioning of it as a statement of the obvious — has three sides.

September 2, 2012

Against Incentivizing Cooperative Strategic Workarounds with Comprehensive Market-Driven Measurables

At the risk of repeating myself, I have to opine that one of Rhode Island's core economic challenges is the frequency of sentences like this:

To position Rhode Island to compete successfully for jobs and investments, a new public/private economic-development partnership should be designed to implement an integrated economic-development strategy that focuses on business retention and expansion, cultivates new business startups, supports a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship, develops market-driven workforce solutions to help grow the middle class, creates a robust research capability to help make better investment and policy decisions, develops a comprehensive manufacturing strategy, aligns state capital programs with economic-development strategies, develops best-in-class business information and knowledge exchanges, provides the highest level of customer service, builds on its regional economic-development assets and actively manages Rhode Island’s image and reputation in the marketplace.

Admittedly, I've been known to write a Melvillian paragraph from time to time, but I always try (at least) to make my endless sentences go somewhere. At a minimum, there should be some humor in there, or a rest-stop of wordplay to persuade the reader that it's worthwhile traveling on — perhaps rereading with justified suspicion that something worth catching might have been missed. But that's 109 words, a full four inches of Saturday Providence Journal column space, of the sort of technocratic jargon that leaves working self-starters rightly convinced that the underlying message is: "You're not included."

(Yes, I measured.)

August 31, 2012

All of Us Are the Job Generators

Although with regret, I have to opine that former East Providence city councilman Robert Cusack misses the target in his op-ed, yesterday, suggesting a way for Rhode Island to rejuvenate its sputtering economy:

We need to identify a job generator, make the changes needed to attract those jobs and then promote Rhode Island to execute the strategy. Which job generator? The initiative that brought Fidelity to the state has worked. Financial services remains a good candidate. Now we hear of bio-science in a new “Knowledge District.” Other ideas have been put forward that capitalize on our strengths. Whichever one or two job generators we target, that decision for once should be data-driven and fully vetted, and not a hipshot. Our future as a state is at stake.

The frame of mind that presents a policy prescription of what "we" (ultimately having to mean the government) need to do is fundamentally built around a trap in logic. Government officials — elected, appointed, or bureaucratic — have no competence in predicting the future bends of the marketplace. Just as the stock market is ultimately a gamble, wagering the state's economic well-being on the probability that the companies that happen to be in Rhode Island will happen to compete well in an industry that happens to take off is a high-stakes bet at best.

August 29, 2012

The Risk of Investment Promises May Be Unhedgeable

Early in the summer, Rhode Island General Treasurer Gina Raimondo announced that the state had invested $900 million of its pension assets in hedge funds. The decision was actually made in the middle of last year, in response to an asset liability study, treasury spokeswoman Joy Fox tells the Current. At that point, the treasurer began accumulating resources in cash to transition it into the new strategy.

August 23, 2012

Umm... Who (and What Policies) Got Us into This Mess?

I've had the extreme good fortune to shift careers to one that allows me time to create and stare at charts. (Sadly, yes, that's a literal description of some of my afternoons, as well as my feelings about those afternoons.) So it's with an especially strong "What!?" that I watched this video, via Ann Althouse, via Glenn Reynolds:

To save time for those who don't want to watch a political ad, the important point is that former President Bill Clinton argues for a second term for President Obama on the grounds that Republicans want to return to an era of deregulation — which, he claims, is "what got us into trouble in the first place." This, he contrasts with the Obama's plan, which "only works if there's a strong middle class." "That's what happened when I was president."

Let me first say that deregulation did play a role in our current predicament, but it wasn't deregulation alone. It was deregulation with a de facto government backing when risky ventures went wrong.

August 18, 2012

What Happens In A Good Economy

It's not that often where I can find an article on CNN.com that has much relevance to Rhode Island, but this one caught my eye. It just shows what a little ingenuity and work can do when you actually have a thriving economy.

Out in North Dakota where the unemployment rate currently sits at 3% due to a new oil boom, a high school student was able to identify a need. Due to the nature of the work and the places that people are living, showers can be hard to come by. Even to the point where people wait hours for a shower at a truck stop. This teen then hatched a plan to purchase an 18-wheeler trailer, retrofit it with shower rooms and an office, and purchase a separate water tank. He offers the service for a fee to the workers.

Sure, I get the point that North Dakota might have gotten lucky with the oil boom. That's like hitting the lottery. But at the same time, the state has been smart enough to simply get out of the way and let the business and entrepreneurs thrive. Business begets business. When you let the market thrive, other businesses will piggyback on top of it and when people perceive a need, they'll work to fill that need.

The other thing that struck me in the article was the kid's attitude with regard to work and money.

Jensen said that while his parents would always be there to assist if he really needed it, the burden of tuition rests squarely on him. He is determined to balance his passion for music with the reality of life."you gotta find something that does." Wow. If you fail at something, keep working to find something else that you can be successful at. That is about as opposite from the "what's in it for me" and the "where's my handouts" attitude that seems so prevalent here in Rhode Island.

"Music is what I absolutely love doing, but for anything in life, if it doesn't pay the bills you gotta find something that does," he said.

North Dakota is about 1800 miles from Rhode Island but judging by the differences in the states, North Dakota might as well be Mars.

August 17, 2012

Other States Need Much More Misery Before RI Has Company

The unemployment rate for Rhode Island fell by one tenth of a percent to 10.8%, but total employment dropped by 80 people. That's not even a "mixed picture," though. The only reason the unemployment rate moved in a seemingly positive direction is that 471 more Rhode Islanders just gave up looking for work.

So if the unemployment rate is a positive sign, then the state's motto might as well be "We hope people leave faster than they lose their jobs."

About the best that can be said for the Ocean State is that every other state in the union lost more employment than it did, except Utah, which saw a slight gain. That context is illustrated very well in an update to my chart showing labor force (employed plus looking for work) and employment for Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut as a percentage of each state's January 2007 labor force.

August 11, 2012

Barro's Welfare Error

Via Ted Nesi comes a Bloomberg column by Josh Barro. It's one of those commentaries in which it isn't quite clear whether the author is offering pure political advice or expressing his opinion, so I'll assume the latter. In that context, here are Barro's thoughts on the balance of the economy and government:

If you concede that the purpose of a business is to provide well-paying jobs and solid benefits, then you cannot defend private equity. Private equity defenders must stand up for the idea that firms do not have a social obligation to retain and pay their employees; their function is to produce products and profits and getting them to do so more efficiently is good for consumers and for the economy as a whole.… [Therefore, it's a] straightforward neoliberal proposition: The government should provide a robust safety net so that employers can be left free to hire, fire, open and close at will. A dynamic private sector is important, but it needs a substantial welfare state to support the people who fall through its cracks.

Barro's is an interesting argument, but its greatest asset is how clearly it brings into focus something that people across the country are beginning to sense, especially on the right: The model of big finance and big business operating to supply wealth, with a robust welfare state picking up the pieces shed in the name of efficiency, is an excellent example of the ways in which the money-shuffling sector is distorting the country's economy and government deleteriously in its own favor.

Barro introduces an error with his most fundamental premise that there is such a thing as one single "purpose of a business." The purpose of a business is whatever the people involved in it want it to be. If they value profit above all else, they'll follow Barro's reasoning; if they value a sense of community, they'll operate differently.

Indeed, the infinite variety of priorities is a large part of what makes people go into one industry or another — or one line of work or another.

August 6, 2012

Recoveries: The Difference the Debt Makes (Not to Mention the Government's Focus)

Earlier today, Glenn Reynolds linked to an American Enterprise Institute post by James Pethokoukis, drawing on charts from economist John Taylor showing that the United States economy hasn't been returning toward where it would have been without the crash, and that this is unusual for prior downturns.

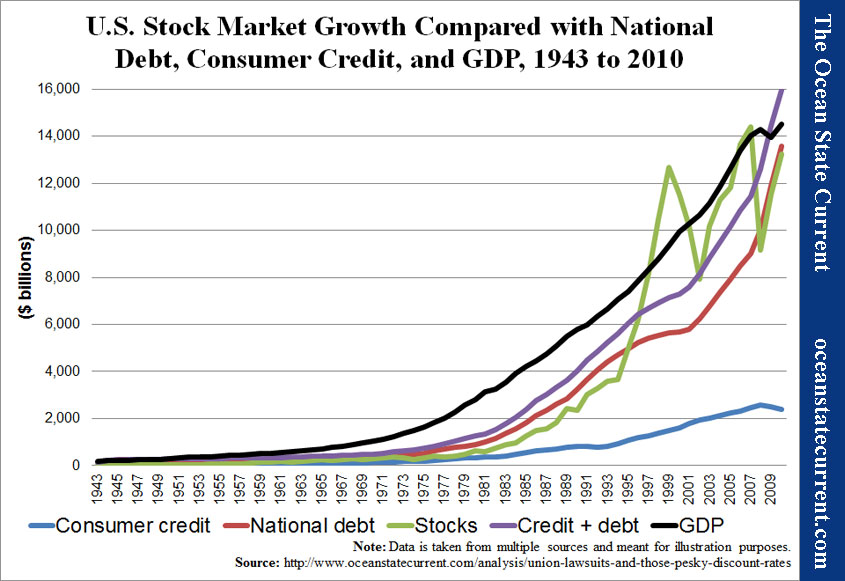

The reasons, I think, can be inferred from this chart, which I created with a view toward answering the question of whether it's reasonable to continue expecting 7-8% returns on pension fund investments:

August 3, 2012

One Graph Says it All

Hm. So what this says is we'd have been better off without the stimulus?

Well, at least we're in our 3rd "recovery summer", 'cause one just wasn't enough!

ADDENDUM: Woops, almost forgot. It's Bush's fault.

August 1, 2012

Hopkins Center Milton Party (and Thoughts on the Fuel of Capitalism)

The Stephen Hopkins Center for Civil Rights' panel discussion on the event of Milton Friedman's hundredth birthday offset "liberaltarian" Brown professor John Tomasi with June Speakman, a Roger Williams professor more inclined to agree with the prefix of the coinage. The panel would have benefited from the inclusion of an unabridged conservative who agreed with its root.

The most interesting idea placed on the Nick-a-Nees table was Tomasi's hypothesis that free markets can correspond with social justice if we think of the latter concept "in new ways." The people who developed social justice, he says, just "happened to be all from the left."

A conservative panelist might have suggested that there's no "happened to be" about it — that the very concept was designed to supplant the competing idea of charity and free association. Justice is the province of the police and the justice system, and "social justice" inherently suggests that those who hold the political levers can judge and impose their view of a just society on others against their will.

Watch video of the event and continue reading on the Ocean State Current...

July 27, 2012

The Context of the President's Context

It's intriguing to observe the telescoping nature of the "context" to which folks are referring when discussing President Obama's infamous Friday the 13th Roanoake speech. The damning two sentences continue to be:

If you’ve got a business -- you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.

The inferred meaning is that somebody else should get credit for the business that you built. The president's defenders introduce the entire paragraph and the next, arguing that the context shows Obama's statement to have been that business owners didn't build the infrastructure on which their businesses rely:

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business -- you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen. The Internet didn’t get invented on its own. Government research created the Internet so that all the companies could make money off the Internet.The point is, is that when we succeed, we succeed because of our individual initiative, but also because we do things together.

The critics expand the text in the opposite direction, to the paragraph before, arguing that the context is, if anything, worse than the gaffe, mainly because of the preachy, scornful tone:

There are a lot of wealthy, successful Americans who agree with me -- because they want to give something back. They know they didn’t -- look, if you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own. You didn’t get there on your own. I’m always struck by people who think, well, it must be because I was just so smart. There are a lot of smart people out there. It must be because I worked harder than everybody else. Let me tell you something -- there are a whole bunch of hardworking people out there.

At this point, as I've argued (and continue to believe), the president's defenders are probably correct on the grammatical point of the key sentence, but his detractors have the better case on the context. In response, a liberal commenter on Anchor Rising criticized me for not including the whole speech. And happy, as ever, to comply, I took a closer look and did indeed come to a striking conclusion: Obama's context is even worse than I'd thought.

July 26, 2012

Talking Teen Unemployment and the Minimum Wage on the Dan Yorke Show

630AM/99.7FM WPRO has posted my appearance on the Dan Yorke show, Tuesday, in two segments. The first is the initial half hour introducing the research from the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity and touching on some conclusions. For the second hour, Economic Development Corp. board member and VIBCO President Karl Wadensten joined us in the studio for a broader discussion.

July 25, 2012

Mancession Recovery... Sexist!

In a strong indication that, among journalistic practitioners, the biased media narrative is more a matter of intellectual laziness than cultural duplicity, the latest canned story, by Los Angeles Times reporter Don Lee, is that workplace discrimination is landing men the great majority of "newly created" jobs:

Since the recession ended in June 2009, men have landed 80% of the 2.6 million net jobs created, including 61% in the last year. ...The gender gap has raised concerns about possible discrimination in hiring. If the trend persists, it could set back gains made by women in the workplace, experts said.

"It's hard to know [whether] some employers place a priority on men going back to work," said Joan Entmacher, vice president for Family Economic Security at the National Women's Law Center. Of particular concern, she said: Opportunities for women in higher-paying fields such as manufacturing are shrinking.

But back in February 2009, even the New York Times had to acknowledge the reality of the male-dominated recession, or "mancession":

The proportion of women who are working has changed very little since the recession started. But a full 82 percent of the job losses have befallen men, who are heavily represented in distressed industries like manufacturing and construction. Women tend to be employed in areas like education and health care, which are less sensitive to economic ups and downs, and in jobs that allow more time for child care and other domestic work.

Of course, Times reporter Catherine Rampell saw the silver lining as women's approaching men's percentage of the workforce. A conservative can't help but think of Margaret Thatcher's criticism of socialists, that they'd be happier to have everybody equally poor than wealthy over wide spectrum.

July 23, 2012

Generations Adrift Without the Habits of Working

One hears anecdotes, from time to time, about young adults who simply do not understand the habits associated with holding a job. Punctuality, an understanding that sometimes tedious or undesirable activities are necessary, and an appreciation of the relationship between consumer and vendor are all examples. Giving young adults the opportunity to learn such principles first-hand is almost as critical as giving them experience with the occupational value of money.

A new paper that I've penned for the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity takes a look at teenage unemployment, with a particular eye on the minimum wage. The upshot is a collapse of employment among the young, especially in locations, like Rhode Island, that can least afford to lose the enterprising inclination in a generation of its residents.

July 20, 2012

Mass Residents Now Visit and Spend More at RI Slot Parlors Than Rhode Islanders

From GoLocalWorcester.

Mass. residents spent close to $1 billion last year at New England casinos, continuing in a trend of increased spending over the past several years that beat out every other state in the area.This year was the first time that the Bay State outspent its neighbors, totaling a cool $909 million on gaming and non-gaming amenities at Connecticut's destination resort casinos and at the slot parlors in Rhode Island and Maine.

Massachusetts residents also, for the first time, out-visited and out-spent Rhode Islanders at Rhode Island's two slot parlors --- Twin River and Newport Grand --- by making 2 million visits to those facilities, and spending an estimated $284 million, which is a 7% increase over 2010 spending levels. Mass. generated more than $157.6 million in tax revenues for the Rhode Island state government.

Some immediate reactions:

> As reflected in disposable income, is this yet another indication of the inadequacy of the Rhode Island economy; in this case - a fair comparison - as measured against a neighbor's economy? A related question: is this yet another indication that Massachusetts is pulling out of the recession faster than Rhode Island?

> What are the implications to Rhode Island's slot parlor revenue stream when the Mass casinos come on line? Perhaps a more accurate question would be: how much further will that revenue stream be stunted now that Mass residents outnumber Rhode Islanders at our slot parlors?

July 19, 2012

Credit for Building, Blame for Dividing

President Obama's teleprompter style has been the subject of substantial (often mocking) critical commentary, and with some justification, as this nearly parodic 2010 video from a Virginia classroom proves:

Given recent political events, one can sympathize with the desire of public officials to avoid extemporaneous speech. In a world in which one's every public utterance can be recorded, scrutinized, and exploited, one can't rely on an audience's capacity to get your drift and give you the benefit of the doubt. And it's all to easy to blurt out a sentence such as the now infamous, "If you've got a business, you didn't build that."

Predictably, in the realm of commentary, the debate has moved to the meta matter of whether commentators are deliberately misconstruing the President's meaning. On Slate, Dave Weigel charitably infers "a missing sentence or clause" that Obama neglected to utter because he was "rambling." On Reason, Tim Cavanaugh rejoins that "at some point it helps to look at that thing above the subtext, which is generally known as 'the text.'"

July 18, 2012

Nationwide Unfunded Pension Liability Now up to $4.6 Trillion

About a month ago, I presented a comparison of estimates for the nation's public-sector pension problem. While none of the results were encouraging, there was huge variation in the degree of frightfulness — the difference mainly being in the way in which they calculate liabilities.

One of the economists, Andrew Biggs, of the American Enterprise Institute, has updated his findings for State Budget Solutions, bringing the highest unfunded liability estimate currently on the table to $4.6 trillion.

July 17, 2012

A Decade of Moving Next Door

I've been following taxpayer migration data for years, but in a haphazard way. A new study that I've coauthored for the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity finally gave me the opportunity to review all fifteen years of available data from the IRS.

The picture — from the 2003 beginning of what can only be described as an exodus — is frightening. After accounting for the tens of thousands of Rhode Islanders who moved to other states and other taxpayers who moved in the opposite direction, Rhode Island lost 24,455 households, with $1.2 billion of annual income (not inflation adjusted). More conspicuously, a net 3,406 taxpayers moved right across the border, to abutting counties in Massachusetts and Connecticut, taking with them $254.5 million in annual adjusted gross income (AGI).

July 12, 2012

RI's Paradox of Being Great, but Still Failing

Remember when the local PolitiFact took the Ocean State Policy Research Institute (OSPRI) to task for claiming that the estate tax was driving Rhode Islanders out, especially down to America's retirement peninsula? One statement from that article has stuck with me, over the year and a half since:

One expert was Kail Padquitt, staff economist for The Tax Foundation, a think tank that studies federal and state tax policies, who said he hasn’t seen any proof that the prospect of paying estate taxes drives people to move."You can see people are leaving a state, but (determining) why they are leaving is hard," Padquitt said. "Florida has sunshine, low taxes and warmth. Why wouldn’t people move there?"

That rhetorical question has come to mind recently for a couple of reasons. For one thing, I've been working on a related bit of research for OSPRI's successor organization, the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity, to be released next week.

Today, though, the quotation came to me in relation to another, separate but related, context. As most folks who follow RI closely have already heard by now, CNBC placed the state dead last (again) on its business friendliness ranking, and very poorly in other areas. Marc Comtois's Anchor Rising post on the subject includes a reaction to RI Future's Bob Plain.

July 7, 2012

Remember when 310,000 new jobs & 5.6% unemployment just wasn't enough? Barack Obama does....

Yesterday we learned that the economy created 80,000 jobs and was at 8.2%, which President Obama called "a step in the right direction". Back in 2004, coming out of a recession, the economy created 310,000 new jobs and unemployment was at 5.6%. But that wasn't good enough--wasn't the real story--for a little-known state legislator running for the U.S. Senate. Instead, then-State Senator Barack Obama criticized then-President George W. Bush and his administration for travelling around celebrating the economic progress indicated by the 310,000 new jobs and 5.6% unemployment rate (h/t).

So remember:

310,000 new jobs and 5.6% unemployment = "too early to celebrate"

80,000 new jobs and 8.2% unemployment = "step in the right direction"

July 5, 2012

The Conundrum of Consumer Bags

So, the town of Barrington is well on its way to banning the use of plastic shopping bags among the commercial establishments within its borders:

... the town conservation commission has already voted to ban the use of plastic grocery bags at retail stores. The proposal now goes before the Town Council for review.If it passes, Barrington would become the second town in New England to impose such a law, increas ingly popular along the trendy West Coast. San Francisco banned plastic bags in large grocery stores and pharmacies in 2007, followed by Oakland and Los Angeles.

The move is triply surreal. For one thing, as American Progressive Bag Alliance spokeswoman argues, "Paper bags are worse for the earth." That is, the ban would be a government restraint on human activity that is at best debatable.

June 18, 2012

Reducing Government Growth isn't Austerity

One meme that some are attempting to make take hold (including the President; "the public sector isn't fine") is that the high unemployment we're seeing is in large part because of the loss of public-sector jobs and especially at the local level:

See that little dip in public sector employment? That right there's you're problem. But, given the 50 year(ish) growth trend, that little dip doesn't seem like much. You see, the greatest portion of governmental growth has historically been at the local level, as this graph from Menzie Chin at the Econbrowser blog shows:

Hm. How to make the argument, then? Ya gotta shape the data! This is how a comparison of private sector to public sector unemployment looks when both are compared to their own relative peak employment (instead of raw numbers), as done by Yale's Ben Polak and Peter K. Schott.

Mon dieu! Look at that, the public sector is going down while the private sector is recovering, just like President Obama said. Yet, as Mickey Kaus explains, the loss of many of these local government jobs can be attributed to the disappearance of federal subsidies:

In this recession, Democrats voted a temporary subsidy for state and local governments to keep up their hiring–and when it expired, those governments found they couldn’t afford to keep on as many employees–especially given the unsustainable pensions and benefits Democrats and others had granted oft-unionized public workers in good times (and that the Dem stimulus subsidized).That's what happened around here when the Department of Labor and Training announced the layoffs of around 60-70 workers. There is also a shift in priorities as older workers retire and aren't replaced. Regardless, the most telling graph shows that it's still the private sector that has bore the brunt of this recession:

We're a long way from saying the private sector is "fine".

May 21, 2012

"A Fast Infusion Of Jobs"

One thing has stuck out to me recently in a couple articles I've read. One article is a couple years old and the other appeared just this past weekend and I think they both make logical mistakes. They both talk about getting Rhode Islanders back to work, yet both are also in fields that I wonder how many new hires are being plucked from the unemployment lines and how many are being taken either from other companies or moved from one project to another.

During the past week, in trying to figure out all this 38 Studios stuff, Ted Nesi sent me an article he wrote in 2010 when the deal was first being done. One part that stuck out to me was this:

Robert Stolzman, a lawyer for the EDC, said last week. "We wanted a fast infusion of jobs in Rhode Island." The number of unemployed Rhode Islanders was 67,500 in August and the jobless rate was 11.8 percent, the R.I. Department of Labor and Training said Friday.However, these aren't the type that someone routinely can pick up after filling out a simple application: