Walter Russell Mead: "Two hundred years ago people thought that the only real jobs involved growing food", by Carroll Andrew Morse

History

11:00 PM, 01/31/13

Happy Thanksgiving!, by Marc Comtois

History

7:00 AM, 11/22/12

The Messiah May Have Used the Word "Wife", by Justin Katz

History

2:07 PM, 09/29/12

The Messiah May Have Used the Word "Wife", by Justin Katz

History

2:07 PM, 09/29/12

U.S. Grant and the Left-Right Lines, by Justin Katz

Blue v. Red

11:35 AM, 09/29/12

Things We Read Today (13), Tuesday, by Justin Katz

President '12

8:34 PM, 09/18/12

Things We Read Today, 8, by Justin Katz

Political Thought

7:11 PM, 09/11/12

Technology and Education Then and Now, by Marc Comtois

Education

12:00 PM, 08/ 2/12

Review: The Price of the Ticket by Frederick Harris, by Marc Comtois

History

9:00 PM, 06/17/12

Happy Presidents Day, by Marc Comtois

History

8:30 AM, 02/20/12

January 31, 2013

Walter Russell Mead: "Two hundred years ago people thought that the only real jobs involved growing food"

Walter Russell Mead, on the relationship between American politics and American society...

Does the American middle class (and by extension, the middle class in other advanced democracies) have a future in a post-blue world? That is the basic question at the heart of American politics;. As I’ve noted, 4.0 liberals think that it doesn’t, and think that the defense of the blue social model is the only way to protect the social achievements of the twentieth century....and on how a future that is different from the present is a source of both hope and fear...They’re wrong. The post-blue future for the middle class is bright, and instead of using the weight of the state to shore up a declining blue system to defend an embattled middle class we need to use that power to promote the transition to a 21st-century political economy and a reinvigorated middle class—larger, richer and more in charge than ever before. This is not a call to dismantle the state; there really are important things that government has to do in a complicated and interconnected society. It’s a call to transform, retool and repurpose the state so that it becomes an engine for progress rather than an anchor trying to hold us in place.

The information revolution destroys jobs, but it also creates them, and we are already in the early stages of a jobs explosion. And as it proceeds, the information revolution is likely to propel the rise of a middle class that is more productive, better educated, more autonomous and more interested in and capable of civic leadership than the Fordist middle class of the late industrial age.The new jobs will be different from the old jobs, and this is one of the reasons many fear the economic transition we’re in. There are a lot of people on both the right and the left who think that in a country that doesn’t “make stuff” there won’t be any jobs. If it isn’t a widget that you can grab in your hand and do something with, it isn’t real. This is nonsense. Two hundred years ago people thought that the only real jobs involved growing food, and that people who made non-necessary consumer goods were engaged in a socially parasitic activity....

The industrial revolution transformed agriculture from the core business of the human race into just one of many things that we do. The information revolution is doing the same to manufacturing....Design, software and engineering become more important as manufacture slips into a secondary status. (We still need factories, just as we still need farms—but fewer and fewer people will be working in them and less and less of our GDP will be bound up in their products.)

November 22, 2012

Happy Thanksgiving!

Given the contemporaneous release of Lincoln, I figured posting our 16th President's Thanksgiving Proclamation seemed appropriate this year:

By the President of the United States

A Proclamation

The year that is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign states to invite and provoke their aggressions, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere, except in the theater of military conflict; while that theater has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defense have not arrested the plow, the shuttle, or the ship; the ax has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege, and the battlefield, and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised, nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American people. I do, therefore, invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a Day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens. And I recommend to them that, while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation, and to restore it, as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes, to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility, and union.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United Stated States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this third day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-eighth.

Abraham Lincoln

September 29, 2012

The Messiah May Have Used the Word "Wife"

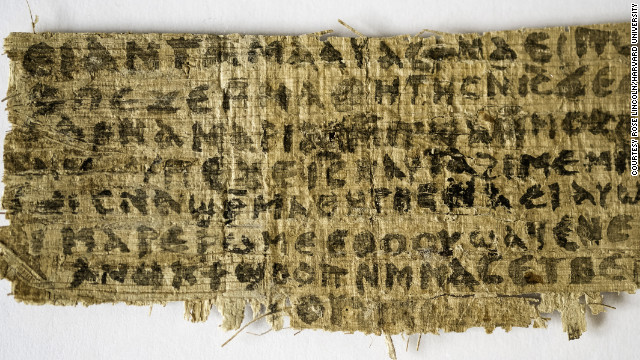

Of one thing, we can be reasonably confident: Coverage of proof and arguments against that sliver of papyrus purporting to prove that Jesus had a wife will have a far smaller profile than the initial boom of proclamations that it had been discovered.

Not surprisingly, the Vatican has stated its opinion that the artifact is "counterfeit," but what I found most interesting about the article is that it's the first time I've seen a picture of it:

I'll confess, off the bat, that I'm not able to read ancient Coptic text, but unless it's a remarkably compact language, that's really not much context on which to come to any conclusions. The paragraph before could have made clear that it was a parable. The paragraph to follow might have been an explanation of the Church's view that it (the Church) is the "bride of Christ." Or the whole thing might be some piece of nefarious propaganda.

I don't know, one way or the other, but the credulity with which such items are passed around is telling, especially with regard to the news media and the stories that it deigns to amplify.

The Messiah May Have Used the Word "Wife"

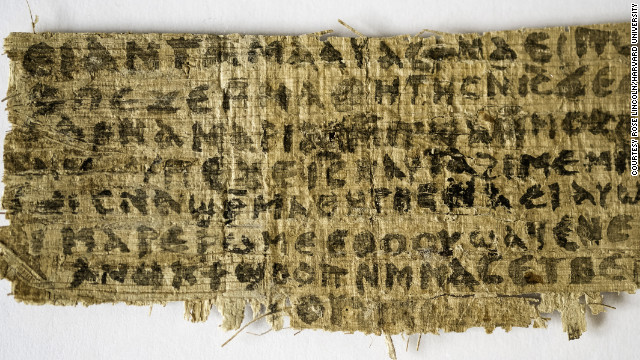

Of one thing, we can be reasonably confident: Coverage of proof and arguments against that sliver of papyrus purporting to prove that Jesus had a wife will have a far smaller profile than the initial boom of proclamations that it had been discovered.

Not surprisingly, the Vatican has stated its opinion that the artifact is "counterfeit," but what I found most interesting about the article is that it's the first time I've seen a picture of it:

I'll confess, off the bat, that I'm not able to read ancient Coptic text, but unless it's a remarkably compact language, that's really not much context on which to come to any conclusions. The paragraph before could have made clear that it was a parable. The paragraph to follow might have been an explanation of the Church's view that it (the Church) is the "bride of Christ." Or the whole thing might be some piece of nefarious propaganda.

I don't know, one way or the other, but the credulity with which such items are passed around is telling, especially with regard to the news media and the stories that it deigns to amplify.

U.S. Grant and the Left-Right Lines

Two lines of debate in the battle of Left versus Right cross frequently.

One is the question of whether history has an inexorable pull toward which it progresses, making it possible for there to be a "right side" of history that one can predict beforehand for a given issue. The other is whether one's side on the issues of the day offers a direct parallel to the sides that one would have taken having born at another period in history.

September 18, 2012

Things We Read Today (13), Tuesday

Days off from retirement in Cranston; the conspiracy of low interest rates; sympathy with the Satanic Verses; the gas mandate; and the weaponized media.

September 11, 2012

Things We Read Today, 8

Today: September 11, global change, evolution, economics, 17th amendment, gold standard, and a boughten electorate... all to a purpose.

August 2, 2012

Technology and Education Then and Now

The family and I recently spent a long weekend in Washington, D.C. and we visited the Smithsonian Museum of American History. The "America on the Move" exhibition included a 1939 Dodge school bus from Martinsburg, Indiana, which served as a platform for explaining how technology (the bus) affected education.

In rural areas, the introduction of school buses changed the character of the communities they served and the lives of the children who rode to school. Students who had once walked to a local, often one-room, schoolhouse now rode a bus to a larger consolidated school where they were taught in separate grades. Progressive educators viewed buses as a step toward modernizing rural education....[and] favored larger schools, arguing they would provide students a better, more standardized education. Some rural citizens feared consolidation would bring higher taxes and a loss of involvement in their children’s education. One midwestern farmer said his local school was “the center—educational, social, dramatic, political, and religious—of a pioneer community.” But declining rural populations and better roads spelled the end of one-room schools. In 1920 Indiana had 4,500 one-teacher schools; in 1945, just 616.I'd say that everyone was right, to a point. At the time, most rural students did benefit from the standardized education (much as did their more urban peers) they attained via a more efficient school consolidation model and better trained, more professional teachers.

Rural folks were correct in that taxes probably did go up to meet the increasing costs of professionalized (and eventually unionized) education. I also don't think that--while the school does still serve as a neighborhood center of sorts (at least in a populous 'burb like Warwick)--many would argue that parental involvement in school has declined precipitously since then.

Fast forward to today and the problems and debates we have with education have less to do with the implementation of a standardized education model than with the very nature of the standards themselves. Indeed, technology continues to play a key role in this contemporary push/pull as, for example, it is the internet upon which ideas such as distance learning and "flipping the classroom" are built and which could lead to, ironically, a less centralized, more student-centered, personalized--versus standardized--education.

June 17, 2012

Review: The Price of the Ticket by Frederick Harris

Fredrick C. Harris is a Professor of Political Science and the Director of Columbia University's Center on African-American Politics and Society. In the world of academia, his racial/political bona fides are beyond reproach. so when he proposes that our first African-American President hasn't adequately addressed racial inequality, it's worth a read. In his Price of the Ticket, Harris explains that the election of President Obama has allowed the country to feel good about itself for choosing a black man as President, even as this President has done little to forward the causes for which so many of his fellow African-Americans have long fought. Harris hopes to put "Obama's race-neutral campaign strategy and approach to governing within the context of history, politics and policy."

Much of the book does just that. Harris spends a few chapters providing historical context that explains the two strategies (and the tension between them) used by African Americans to achieve political power:

The coalition-politics perspective calls on black voters to build coalitions with whites and other racial and ethnic groups to develop support for issues and policies that help most everyone. The independent-black-politics perspective presses blacks to work independently of other groups to push for community interests with the aim toward building support with other groups around both universal policies and community-specific issues.Harris' telling of the evolution of these strategies over the decades is an interesting story and he provides valuable insights as to how the political campaigns of Shirley Chisholm, Jesse Jackson and the late-Chicago Mayor Harold Washington laid the groundwork for Obama's successful 2008 run for the Presidency. Focusing on Obama, Harris contends that the race-neutral politics of the President--which go hand-in-hand with coalition politics--"has marginalized policy discussions about racial inequality."

Proponents of "race-neutral" universalism fail to acknowledge that policies that help everyone--what can be described as a trickle-down approach to eradicating poverty and social inequality--are not enough to correct the deep-rooted persistance of racial inequality. In many ways, the majority of black voters have struck a bargain with Obama. In exchange for the president's silence on community-focused interests, black voters are content with a governing philosophy that helps "all people" and a politics centered on preserving the symbol of a black president and family in the White House.This is the "price of the ticket" and it's clear that Harris is no proponent of coalition-politics. To bolster his point, he contrasts the gains made by the LGBT community under the Obama Administration to the lack of progress made on racial equality. The former, Harris contends, has kept the pressure on Obama (as has, according to Harris, the Tea Party) and been rewarded while the black community has given the President a pass, a dynamic he delves deeper into in his chapter, "Wink, Nod, Vote."

Further, Harris argues that Obama has become a "hollow prize" for Black America because the President has been forced to contend with an economic downturn instead of turning his attention to implementing policies--however modest--that dealt with racial inequality. Worse yet, by Harris' contention, Obama hasn't adequately addressed inequality even within the context of the economic downturn. When asked in 2009 about the "mounting problem of black unemployment" and why he hadn't targeted it:

Obama provided the same pat answer. Obama acknowledged that black and Latino workers were disproportionately affected by the great recession, but he still insisted that policies that helped everyone would cure the catastrophic unemployment rate in minority communities.This was in contrast to a proposal by the Congressional Black Caucus, for instance, that:

...incorporated the principle of "targeted universalism"; an approach that would geographically target government-sponsored job projects in communities most affected by the recession and with the greatest concentrations of poverty. By default, such legislation would not help everyone equally but benefit those most affected by the recession.In other words, blacks and other minorities.

In a comparison between Herman Cain (running for the Republican Presidential nomination at the time Harris' was writing the book) and President Obama, Harris finds that both fall short of the promise that politically powerfull African-Americans are supposed to fulfill.

When you place Cain next to Obama, who appears to be too timidly strategic to raise questions about--and work overtly against--racial inequality, the actions (or in the case of Obama inactions) of both diminish black interests on the national political scene. One black candidate for president spouts bigoted views about blacks and the poor. The other is silent on issues of racial inequality and poverty. In the end, neither political party is a vehicle for blacks to directly confront inequality, because both parties push black-specific issues to the margins of national policymaking. This development tells us something about the durability of racism as an ideology in American politics. Instead of fading away in an era celebrated as "postracial," race as ideology demonstrates convincing staying power, endowed with the ability to readapt and readjust as new political situations arise. {emphasis added}Thus, we see that Harris' critique of Obama is rooted in his apparent belief that America, as whole, is still a racist society. By Harris' interpretation, electing a black man president is not to be taken as a symbol of the end of widespread, institutional and cultural racism, but rather a signal that such racism has changed and "readjusted."

The problem is that his interpretation is based on his contention that Obama hasn't done enough to address what Harris refers to--multiple times--as racial inequality. Yet, he never truly defines that inequality and the reader not versed in contemporary African-American politics is left wondering, "so what could Obama do in the realm of addressing racial inequality that will make Harris happy?"

Harris does spend time giving examples of, and discounting, what he calls the "politics of respectibility" (Bill Cosby comes in for some criticism on this front). But without more specificity as to what policies Harris supports towards racial equality, as opposed to explaining what he doesn't support, we are left guessing. In the end, Harris has provided a fine history of the development of contemporary black political strategies. He is less convincing in supporting his contention that President Obama's decision to govern America as a coalition--and not focus on acute issues affecting African-Americans--marks Obama as a failure as an African-American president. As a result, we're just not sure, exactly, what President Obama could have done to have been a success in Harris' eyes.

February 20, 2012

Happy Presidents Day

I had thought about pointing to a few articles on presidential rankings made by historians or political scientists. But, really, we know they're biased (heck, they ranked President Obama #15 overall after 18 months in office!), so I'll just leave you with this link to a Wikipedia article on the subject that also includes a handy and sortable aggregate ranking table.

Rankings don't mean agreement with ideology or politics, just recognition of their effectiveness at what they wanted to do combined with how well they governed. For my money, I still put ol' GW as #1. Thanks to him, the whole idea that the President isn't a king took hold (though FDR would have kept going if he hadn't died, methinks). I have a soft spot for John Adams, but, frankly he wasn't a good President even if he was a helluva character. Lincoln, for me, is a close #2--he guided our nation through it's toughest times. After that, we get into tiers--Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt, FDR; Madison, Jackson, Truman; Reagan, Wilson, Polk--etc. Obama isn't in the top half in my book--I'd put Clinton ahead of him for instance--but I still think he's ahead of Carter!

Who's your favorite?

January 18, 2012

RE: Life Before Entitlement - Historical Perspective

The article to which Justin referred discusses the mutual aid societies that cropped up during the late 19th and early 20th century to deal with poverty and other social issues. Historian Walter Trattner, author of From Poor Law to Welfare State, was quoted in the article:

Those in need. . . looked first to family, kin, and neighbors for aid, including the landlord, who sometimes deferred the rent; the local butcher or grocer, who frequently carried them for a while by allowing bills to go unpaid; and the local saloonkeeper, who often came to their aid by providing loans and outright gifts, including free meals and, on occasion, temporary jobs. Next, the needy sought assistance from various agencies in the community–those of their own devising, such as churches or religious groups, social and fraternal associations, mutual aid societies, local ethnic groups, and trade unions.Anecdotally, I know this to be true in my own family. My grandparents owned a small general store in northern Vermont and many was the time when they carried people going through a rough spot. (After he died, my grandfather's papers included more than a few uncollected IOUs, including property or farm deeds). The sense of community was very real and aid societies were comprised of such like-minded individuals who bonded together to help their neighbors and those in need.

A good paper on the topic was written by Dave Beito.

Continue reading "RE: Life Before Entitlement - Historical Perspective"January 2, 2012

History Bits

Here are a few historical items I've come across that piqued my interest (but not enough to devote a whole post).

In the wake of "tree gate" and all the Roger Williams talk, wouldn't you know a new book is out about him? Read an excerpt, an interview with the author and a review.

This piece from 2010 by Scott McKay on "Fighting" Bob Quinn is worth reading for those who'd like more insight into Rhode Island political history and (the legacy we still live with!).

On a lighter note: If, like me, a lot of your early reading was done via the pages of comic books, you may recall Classics Illustrated. Now they're online. If you like Fighting Bob Quinn, you'll love Fightin' Abe Lincoln!

More seriously, "Why Irish soldiers who fought Hitler hide their medals" was one of those items that had me shaking my head. In the wake of gaining their independence, I understood how the Irish continued to loathe Great Britain and that this led to Ireland being neutral during WWII. I didn't know they treated the returning war veterans (albeit technically they were "deserters") like pariahs.

Finally, I recently re-read Bernard Bailyn's To Begin the World Anew, a book of essays (it's short) concerning the American founding. I highly recommend--a good library pick. Here's the introductory essay (in a slightly different form than that found in the book).

In the most general sense, what stimulated the Founders' imagination and hence their capacity to begin the world anew was the fact that they came from outside the metropolitan establishment, with all its age-old, deeply buried, arcane entanglements and commitments. From their distant vantage point they viewed what they could see of the dominant order with a cool, critical, challenging eye, and what they saw was something atrophied, weighted down by its own complacent, self-indulgent elaboration, and vulnerable to the force of fresh energies and imaginative designs. Refusing to be intimidated by the received traditions and confident of their own integrity and creative capacities, they demanded to know why things must be the way they are; and they had the imagination, energy, and moral stature to conceive of something closer to the grain of everyday reality, and more likely to lead to human happiness.

December 7, 2011

Would Roger Williams Have Called it a Holiday Tree II

Yes, there are many other issues in the world to be discussed, but there has been so much rote recitation of bad history in the coverage of the Rhode Island statehouse "holiday" tree, it is worth repeating that views never held by Roger Williams routinely are attributed to him. The latest, perhaps most direct, example comes from a former director of the Rhode Island Historical Society, quoted in Paul Davis' Projo article on yesterday's statehouse event celebrating a cluster of holidays that recur in month 12...

[Governor Lincoln Chafee] says his decision honors the state’s origins as a sanctuary for religious diversity. Roger Williams founded Rhode Island in 1636 as a haven for tolerance and insisted government and religion remain separate, he says.Actually, Mr. Klyberg is incorrect. As Marc has pointed out, Rhode Island's colonial charter, strongly influenced by Williams, did not require that religion be removed from the public square. And in one of his most famous expositions of his own ideas, "The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience", Roger Williams expressed no opposition to introducing a religious dimension into government business, when offering specific counsel to civil leaders on the matter of religion. In fact, just the opposite was true...Rhode Island historians say Chafee’s interpretation of Williams is correct.

“If Roger Williams was alive today, he would not refer to it as a Christmas tree,” says historian Albert Klyberg, a former director of the Rhode Island Historical Society. “Williams was very much opposed to introducing religious elements into public business.”

The civil magistrate either respecteth that religion and worship which his conscience is persuaded is true, and upon which he ventures his soul; or else that and those which he is persuaded are false.Approbation (I had to look it up) is approval, usually with the connotation of officialness; there is no meaningful connection to be drawn from Roger Williams' advice "that religion and worship which [a] conscience is persuaded is true" be countenanced and approbated by civil authority, to separating religion from public or even government celebrations.Concerning the first, if that which the magistrate believeth to be true, be true, I say he owes a threefold duty unto it:

First, approbation and countenance, a reverent esteem and honorable testimony, according to Isa. 49, and Revel. 21, with a tender respect of truth, and the professors of it...

Day of Infamy

With the 70th Anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, it feels like the passing of an age is upon us. Fewer and fewer of those alive during those times--particularly those who fought--are still alive today. It seems the emotional resonance that past remembrances of the "day that will live in infamy" began to dampen over the last few years, particularly as we live in the shadow of our own more contemporary tragedy of 9/11. Nonetheless, brave men fought and died for our nation on December 7, 1941 and their sacrifices should not be forgotten.

November 17, 2011

The Cultural Cycle We're In

Commenting on the image cut by "union protesters" (that is, protesting union members), Alice Losasso of West Warwick quotes Scottish historian Alexander Tytler as follows:

"The average age of the world's greatest civilizations from the beginning of history, has been about 200 years. During those 200 years, these nations always progressed through the following sequence: From bondage to spiritual faith; From spiritual faith to great courage; From courage to liberty; From liberty to abundance; From abundance to complacency; From complacency to apathy; From apathy to dependence; From dependence back into bondage."

I'd like to think that the cycle can be broken, but I'm not so sure. As Tytler indicates in the preceding paragraph, the forces pushing toward decline control the vote because they get goodies from the system. The topic brings to mind a comment that Phil left yesterday to one of my pension posts:

I think it is appropriate to try to stifle reform that targets aging retirees. Do you want your generation to be the one that breaks contracts and faith with your elders once they have stopped working?

My "elders" fashioned the yoke of government regulation and inside dealing that is strangling our economy; they set fire to the cultural pillars that must stand in order to sustain liberty and abundance over the long term; they worshiped their own untrammeled independence to such a degree that they failed to reproduce in sufficient numbers to maintain the Ponzi schemes that they developed; and they made themselves promises at the expense of those whom they deigned to beget. The generation that once declared, "don't trust anyone over 30," is now insisting, "don't discomfit anyone over 60."

For my part, I'm utterly unpersuaded that those now approaching middle age, much less those who are younger still, are therefore obligated to maintain the scheme. There is no moral obligation for a young, struggling family to ensure a cushy retirement that maintains an arbitrarily high standard of living for people who have ceased to produce. But to enforce that obligation, and others like it, my "elders" will be only too happy to place increasing power in the hands of an incompetent governing class that will persist long after the gray years of the Boomers — probably until the entire civilization collapses or a bloody revolution sets things aright. From my perspective, some rational, not-exactly-arduous reforms now would be preferable.

ADDENDUM.

Russ was happy to point out in the comments that the Tytler quotation is actually a common misattribution. That's fine. Just as I wouldn't argue that a cultural observation must be true because some historian made it, I won't discount that it might be true even if he didn't say it, especially for use in a more philosophical-type blog post.

September 8, 2011

Teaching September 11th

In the Valley Breeze today, I was happy to read that the Lincoln Middle and High Schools will be teaching the events of September 11, 2001 to the students. The part that disappointed me a bit was that they will be talking about it with the students, for the first time.

"[LHS Principal Kevin] McNamara said that LHS has not done anything like this in the past, but he decided to for this milestone year. "With the 10-year anniversary, it has refocused everyone on the importance of memorializing the event," McNamara said."

I remember after it happening, wondering how schools were going to teach this. When I was in school, we learned about D-Day, we learned about Pearl Harbor, we also talked about the Vietnam conflict. So how would schools teach about what happened on that perfectly clear Tuesday morning ten years ago now. Apparently, the answer is they don't. They don't want to talk about the gruesomeness of it, they don't want to talk about the fear of flying a commercial airplane or being in a tall building and wondering if anything will happen to it. They don't want to scare the children.

I did some more searching on how the subject is taught in schools and why it isn't taught in many places and found this one explanation:

"With no standard curriculum in place, teachers across the country have been forced to develop their own methods to talk about the traumatic events of the past decade in the classroom. Many have turned to privately created lesson plans"

"forced to develop their own methods"? Isn't that what they do? Teachers are professionals and in their training, they learn how to develop a lesson plan in their subject area. I'm not sure why teachers can develop a plan for how to teach this part of history in the same ways that they develop lessons to teach algebra, diagramming sentences or the FDR presidency. When these things aren't taught, a very important part of our history is lost on the students, even to the point where people from their mid-twenties on up might want to bang their head in frustration.

Back in May, the Yahoo search blog wrote:

However, it seems teens ages 13-17 were seeking more information as they made up 66% of searches for “who is osama bin laden?”

That just shouldn't even be possible. Our schools should be spending more than a day or two on the subject. This is a topic that could go for an entire semester or even an entire year, so to talk about it in the schools for just a day or two around the anniversary of the attacks doesn't do the history justice. The Middle East and the US' involvement is something that will probably be a topic of discussion for the entire lives of today's students. To not even talk about it in schools is irresponsible.

June 30, 2011

Arbitration and History

Marc and Matt Allen continued the conversation about binding arbitration on last night's Matt Allen Show and went on to talk a bit about Michelle Bachmann. Stream by clicking here, or download it.

June 29, 2011

About Bachmann's "Founding Father's fought Slavery" statement

Apparently we're at the point in Campaign 2012 where we play the game of dissecting political statements for "gotcha moments." The pols have to be ready for the questions, so they should work to make sure they mitigate damage by reading up beforehand. That being said, of all the things to talk to a Presidential candidate about, why focus on interpretations of who exactly was a Founding Father? But, since it was broached....

The question, from ABC's George Stephanopoulos, and Bachmann's answer:

Stephanopoulos: [E]arlier this year you said that the Founding Fathers who wrote the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence worked tirelessly to end slavery. Now with respect Congresswoman, that’s just not true. Many of them including Jefferson and Washington were actually slave holders and slavery didn’t end until the Civil War....First of all, because "some" Founders had slaves doesn't mean that "some" didn't fight against slavery. This isn't an "either or" kinda thing. Besides, someone else offered an opinion on this (H/t)Bachmann: Well if you look at one of our Founding Fathers, John Quincy Adams, that’s absolutely true. He was a very young boy when he was with his father serving essentially as his father’s secretary. He tirelessly worked throughout his life to make sure that we did in fact one day eradicate slavery….

Stephanopoulos: He wasn’t one of the Founding Fathers – he was a president, he was a Secretary of State, he was a member of Congress, you’re right he did work to end slavery decades later. But so you are standing by this comment that the Founding Fathers worked tirelessly to end slavery?

Bachmann: Well, John Quincy Adams most certainly was a part of the Revolutionary War era. He was a young boy but he was actively involved.

Who were our fathers that framed the Constitution? I suppose the "thirty-nine" who signed the original instrument may be fairly called our fathers who framed that part of the present Government. It is almost exactly true to say they framed it, and it is altogether true to say they fairly represented the opinion and sentiment of the whole nation at that time. Their names, being familiar to nearly all, and accessible to quite all, need not now be repeated....Thanks for clearing that up, Mr. Lincoln.In 1784, three years before the Constitution - the United States then owning the Northwestern Territory, and no other, the Congress of the Confederation had before them the question of prohibiting slavery in that Territory; and four of the "thirty-nine" who afterward framed the Constitution, were in that Congress, and voted on that question. Of these, Roger Sherman, Thomas Mifflin, and Hugh Williamson voted for the prohibition...[t]he other of the four - James M'Henry - voted against the prohibition, showing that, for some cause, he thought it improper to vote for it.

In 1787, still before the Constitution, but while the Convention was in session framing it, and while the Northwestern Territory still was the only territory owned by the United States, the same question of prohibiting slavery in the territory again came before the Congress of the Confederation; and two more of the "thirty-nine" who afterward signed the Constitution, were in that Congress, and voted on the question. They were William Blount and William Few; and they both voted for the prohibition...This time the prohibition became a law, being part of what is now well known as the Ordinance of '87....

In 1789, by the first Congress which sat under the Constitution, an act was passed to enforce the Ordinance of '87, including the prohibition of slavery in the Northwestern Territory. The bill for this act was reported by one of the "thirty-nine," Thomas Fitzsimmons, then a member of the House of Representatives from Pennsylvania. It went through all its stages without a word of opposition, and finally passed both branches without yeas and nays, which is equivalent to a unanimous passage. In this Congress there were sixteen of the thirty-nine fathers who framed the original Constitution. They were John Langdon, Nicholas Gilman, Wm. S. Johnson, Roger Sherman, Robert Morris, Thos. Fitzsimmons, William Few, Abraham Baldwin, Rufus King, William Paterson, George Clymer, Richard Bassett, George Read, Pierce Butler, Daniel Carroll, James Madison.

Is this a stretch? Perhaps, but no more, really, than the gymnastics that Stephanopoulos went through just to get to this point.

March 14, 2011

An Invitation to Michele Bachmann

On behalf of no recognized or legitimate authority whatsoever (i.e. staying true to my blogging roots), I invite United States Congresswoman and possible long-shot Presidential Candidate Michele Bachmann to round out her knowledge of New England history by paying a visit to my neighborhood, the Edgewood and Pawtuxet sections of Cranston and Warwick, Rhode Island, during the second weekend of June, where she can watch the annual reenactment of the burning of the HMS Gaspee -- sometimes referred to as "the first blow for freedom" struck by the American colonies against the British -- and perhaps meet a few folks who will be able to convince her that not everyone in New England outside of New Hampshire is part of a monolithic political culture (although we understand how non-New Englanders might sometimes see it that way time), and that there's still much life left in Alexis de Tocqueville's observation that New England is the home to the closest thing to the democratic (small-d) ideal that the modern world has ever seen.

February 16, 2011

Fordham Institute Reports on the State of U.S. History Standards (Except Rhode Island)

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute has studied various State-level U.S. History Standards and come up with a report (PDF). For the most part, they didn't like what they found with a "majority of states’ standards are mediocre-to-awful." And, surprise, of all the states, Rhode Island was the only state to receive an N/A (Incomplete). Why?

As of 2010, Rhode Island has chosen not to implement statewide social studies standards....Rhode Island expressly declares its GSEs [Grade Span Expectations...for Civics & Government and Historical Perspectives/Rhode Island History] not to be general social studies or history standards, it would be inappropriate to review them as such.Perhaps once Rhode Island implements the Common Core standard we'll have an analysis-worthy standard in place (though I think the initial emphasis is on Math and ELA). Until then, it looks like RI shares the same core problem with History standards with most of the rest of the states across the country. According to Fordham, this is the "submersion of history in the vacuous, synthetic, and anti-historical 'field' of social studies." They quote Dianne Ravitch.

What is social studies? Or, what are social studies? Is it history with attention to current events? Is it a merger of history, geography, civics, economics, sociology, and all other social sciences? … When social studies was first introduced in the early years of the 20th century, history was recognized as the central study of social studies. By the 1930s, it was considered primus inter pares, the first among equals. In the latter decades of the 20th century, many social studies professionals disparaged history with open disdain, suggesting that the study of the past was a useless exercise in obsolescence that attracted antiquarians and hopeless conservatives. (In the late 1980s, a president of the National Council for the Social Studies referred derisively to history as “pastology.”)They also criticize "overly broad content outlines" ("isolated fragments of decontextualized history") and the practice of chopping up historical periods across grade levels, which leads to different levels of historical inquiry based on grade level. They also find that there is too much ideological pollution finding its way into History curricula. Continue reading "Fordham Institute Reports on the State of U.S. History Standards (Except Rhode Island)"

February 13, 2011

Sunday Book Review: A Slave No More

A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation by David W. Blight.

A Slave No More is many books in one. The heart and soul of the work are the never-before-published emancipation narratives written by Wallace Turnage and John Washington. Blight provides historical context by matching their individual stories to the Civil War time line and compares them to other emancipation narratives. In essence, Blight provides the historical skeleton upon which the Turnage and Washington stories are overlayed.

In the first two chapters, Blight provides the historical context and his analysis of Washington and Turnage narratives, respectively. His discussion of the different nature, tone and goals of antebellum and post-bellum emancipation narratives is important.

Antebellum slave narratives tended to conform to certain structures and conventions. Given the depth of racism in the era, rooted in assumptions of black illiteracy and deviance, pre-1860 ex-slave autobiographers had to demonstrate their humanity and veracity. They had to prove their identity and their reliability as first-person witnesses among a people so often defined outside the human family of letters….Most narratives were cast as contests between good and evil, moving through countless examples of cruelty toward slaves and ending in a story of escape. Many are essentially spiritual autobiographies, journeys from sinfulness and ignorance to righteousness and knowledge. On one level, antebellum slave narratives were effective abolitionist propaganda, condemnations of slavery in story form.According to Blight, the Washington and Turnage narratives are unique because they exhibit qualities of both ante- and postbellum types.Post-emancipation slave narratives, however, changed in content and form. They still tend to be spiritual autobiographies, often by former bondsmen turned clergymen, and they were written in the mode of “from slave cabin to the pulpit.” But postslavery narratives are more practical and less romantic, more about a rise to success for the individual and progress for the race as a whole….It is not so much the memory of slavery that matters in the bulk of the postwar genre, but how slavery was overcome by a narrator who competed and won his place in an ever-evolving and more hopeful present. Slavery is now a useable past in the age of Progress and Capital….Antebellum narratives are saturated with the oppressive nature of slavery and a world shadowed by the past. Postbellum narratives reflect backward only enough to cast off the past, exalt the present and forge a future.

In the third chapter, Blight describes how he used various resources to rediscover Washington and Turnage’s past. It is a good object lesson to future historians as to the twists and turns—some frustrating, some unexpected--that research can take. In chapter four, Blight tackles the larger historiographical question of emancipation and whether it was bottom-up or top-down. It was both:

Emancipation in America was a revolution from the bottom up that required power and authority from the top down to give it public gravity and make it secure. Freedom, as Lincoln said, was something given and preserved, but it also, as he himself well understood had to be taken and endured. And it ultimately was fostered by war and engineered by armies.In this chapter, he also charts the origin of the “faithful slave” myth and the important part it played in the “Lost Cause” narrative that arose in the postbellum south.

The final two chapters are the emancipation narratives themselves. Both writers apologized for their poor writing skills, yet, while they did write simply, they also wrote engaging and sometimes eloquent prose. In addition to having a talent for description, both were skilled at using humor (sometimes dry) and irony to make their point. For instance, Turnage, in explaining--upon overhearing that he was due a whipping from an overseer--decided not to wait around, so he “got over the fence to see what would be the result.” That’s one way of explaining that he ran away!

In sum, whereas Blight--as he describes--may believe that he was simply in the right place at the right time to have had these works fall into his lap, he has done a magnificent job of presenting the Turnage and Washington stories within their proper historical context. This is a valuable work of history.

A version of this review was originally posted at Spinning Clio on 1/13/2008.

February 6, 2011

Book Review: From Battlefields Rising

Note Bene: One of the ancillaries of having a history blog was receiving, from time to time, a review copy of a book from its publisher. Well, although the aformentioned blog is now dormant, I still occasionally receive books and I think offering the occasional Sunday review seems appropriate. Life is more than politics and culture wars and sometimes taking a breath and writing about something else--and throwing it up here--is worthwhile all its own. At least, I hope you all agree.

From Battlefields Rising: How The Civil War Transformed American Literature, by Randall Fuller. Oxford University Press, Inc. New York, NY, 2011.

Fuller's aim is to explore how the Civil War affected leading writers of antebellum America such as Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Herman Melville. Sometimes we forget how clustered these writers were: all in the Northeast, particularly New England, and many in Concord, MA. This geographic closeness had some influence on their philosophical and political views, too.

Chiefly, most of these 'transcendentalists' (if not all) were avidly abolitionist. Most had advocated for this cause and, at the outbreak of the Civil War, were sure of both its rightness and the relative ease--so they believed--with which it would be attained. Their moral clarity would become clouded to one degree or another as the casualties mounted and the war dragged on. Fuller investigates these various crisis' of conscience and the questions that arose.

For instance, at the outbreak of the war Walt Whitman was attempting something of a literary comeback. A pair of young Boston publishers had sought him out to publish the next edition of his Leaves of Grass (something he would update throughout his life), which had opened with his poetic paradigm shifting "Song of Myself." It was from this "Song" that Whitman seemed to draw inspiration for much of his latest work--poems that ruffled Victorian-era feathers and substantiated Whitman's notoriety. Yet, his infamy was shortlived with the outbreak of war. The reading public became interested in news and writings that dealt with it and little else. Even the various writers of the time found their focus shifting and Whitman's own optimism about the war was permanently affected by the tragedy of the Battle of Bull Run, which would resurface in his writing again and again.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was also profoundly affected by the war. A writer of romances who had been abroad for many years, he returned to Concord, Massachusetts in the months preceding the war to find a changed and radicalized town. For while he certainly agreed with abolitionist goals, he didn't approve of their approval of John Brown and his actions. Unlike the rest of Concord's leading lights, Hawthorne felt, according to Fuller:

Brown's actions...begged questions of morality that were too easily obscured by the transcendentalists' lofty rhetoric. How could the man's admirable vision of slavery's wrongs ever justify his murderous actions? Didn't the deaths of soldiers, innocent bystanders, and his own men negate the righteous imperatives Brown felt he represented? And how could responsible thinkers so blithely excuse these consequences?Hawthorne simply couldn't relate. He published an essay in the Atlantic, "Chiefly about War-Matters" that posed many of these same questions and caused a ruckus amongst his neighbors. As Fuller explains, the essay was accompanied by critical footnotes by the Editor--who was Hawthorne himself! No one was immune to Hawthorne's problematic probing. As for his career, Hawthorne had returned to Concord with hopes of completing another great novel, but he found trouble focusing because of the war and eventually gave up hope of completing it. He died shortly thereafter. As Fuller eulogizes, "For Hawthorne, the war...had doused a fervent literary imagination, ended an illustrious career."

Others were affected in varying degrees and in different ways. Emily Dickenson watched her male acquaintances and relatives march off to war and her poems came to include more references to the conflict and its results: death and maiming. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in the wake of the burning death of his wife, turned to translating Dante's Divine Comedy, which was itself written during a period of civil war in Tuscany. Herman Melville actually participated in the war, briefly (and the episode would influence his Billy Budd, a Sailor many years later), but he spent most of his time compiling his Battle Pieces, in which, according to Fuller, "[He] insisted...the war might have been avoided if both sides had been less rigid and unyielding in their convictions." The work was published a year after the war (1866) and sold less than 200 copies. As Fuller no doubt correctly surmises, "Tired of war, Americans were certainly not interested in ambiguity or self-questioning."

The literary and personal insights provided by Fuller are interesting and provocative. One can't help but trace the war-time evolution of these writers' feelings, thoughts and works and compare them to those of the contemporary media and even ourselves. There is also some solace to be gained from learning that even literary giants who supported as modernly uncontroversial a cause as the abolition of slavery would have flawed conceptions about the ease with which it could be accomplished and would come to have some reservations concerning the vehicle by which it was ultimately attained. In short, they were human, just like us.

January 26, 2011

Principles Opposed to Slavery and Statism

Once again, I find I must recommend an inaccessible article in National Review, this one by Gettysburg College history professor Allen Guelzo:

The antidote to slavery, Lincoln insisted, was also economic free labor. In the 19th century, free labor was the shorthand term for a particular way of viewing capitalism: as a labor system, in which employers and employees struck bargains for production and wages without restriction and where the boundaries between these two roles were fluid enough that today's employee could, by dint of energy, talent, and foresight, become the employer of tomorrow.Slavery was the polar opposite fo free labor. With very rare exceptions, it denied the slave any future but that of being a slave, and it replaced the open-ended arrangements of employees and employers with a rigidly dictatorial system. The harmful effects extended beyond the slaves themselves, Lincoln wrote, because in the process, all labor became stigmatized as "slave work"; the social ideal became "the gentleman of leisure who was above and scorned work," rather than "men who are industrious, and sober, and honest in the pursuit of their own interests." Men who are industrious — that, of course, described Lincoln. Slavery, then, was not merely an abstraction; it was the enemy of every ambition Lincoln had ever felt.

Especially interesting are the links that Guelzo implicitly draws between the social system built on American slavery and a social system built on statism. For one thing, both characterize a relationship of freely exchanged employment as its opposite:

Lincoln was aware that pro-slavery propagandists had begun claiming in the 1850s that laborers in northern factories were, in reality, no more free to make wage bargains than slaves on southern plantations. In fact, they claimed, "free labor" was worse off, because employers had no obligation to provide health care for mere wage-earners or to support them in childhood and old age, the way slaveowners did for their slaves.

Not for no reason, then, did the Confederate government organize itself in line with the principles of its guiding institution:

... while the Union government contracted out its wartime needs to the private sector, the Confederate government set up government-owned supply facilities...

Historian Raimondo Luraghi called it "quasi-socialist management."

Despite the links between slavery and statism, two considerations have to taken into the balance, one qualifying the case of the former, the other the case of the latter. First, the slave-based system, here, is specifically that of the mid-to-late 1800s — the last guard, as it were, striving to maintain the system. In prior eras, slavery was simply a fact of life coexisting, however discordantly, with evolving notions of liberty.

Second, statists often begin with the well-being of the lower classes primary in their minds. In that respect, their views are opposite those of slaveholders. What unites them is the notion that the great majority of human beings are better off letting experts with centralized authority govern their lives. No matter the impetus, that sounds like slavery to me, no matter how beneficent.

January 8, 2011

Taking the GG Out of Literature

During my time as a college English student, with professors being predictably as you can imagine they were, I was struck by how powerful a set of letters "nigger" could be — first, as a dehumanizing attack and, later, as a literary marker of the speaker's ignorance. Particularly in postbellum literature, and especially in certain fonts, that double-g looks like a dark jab scattered across the page. Whether the book that first gave me that impression was something by William Faulkner or was Huck Finn, I don't recall, but it came to mind upon reading of an edition of Mark Twain's book that replaces all instances of the word with "slave."

As Twain once said, "the difference the almost right word & the right word is really a large matter — it's the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning."

Rich Lowry has posted a letter that makes the point well. Readers of Huck Finn can't help but discern the author's criticism of those using the word, and the callousness of their attitude toward human life. There's a callousness to removing the word, as well.

My reading of the book, which I described in academic detail in the essay that kept me out of Brown University's graduate program in Literature, makes this point central to a sly, more intriguing intention that I believe to have been Twain's underlying purpose for the book. Addressing longstanding and heated disapproval of Twain's reintroduction of Tom Sawyer for the climax of the book — which has led multiple critics to declare the ending an unforgivable failure, with no less a figure than Ernest Hemingway calling it "cheating" — I proposed that Twain was putting the reader in the position of the character of whom he or she was apt to be most critical:

When it is considered that, at Huck's moral juncture, Tom comes into an adventure in progress with privileged information, a new link is seen: this time to the reader. Tom's reappearance for the Phelps section does lead to a change in the book (as is evident from the controversy over the end), but only inasmuch as we were expecting (read "hoping") for something different. A reader hoping to read a Jim-as-hero-escaping-from-slavery story would be, essentially, hoping to do (or hoping that the author does) exactly what Tom tries to do from his point of view: make the book interesting in a certain way, in part by making Jim into a specific type of hero. In the Connecticut of the 1880s, this would translate into a desire to "set [Jim] free" even though "he was already free" (Twain, 262). It is not necessarily requisite to this conclusion that the reader of this, or our, era would see Jim, specifically, as free; it is enough that the post–Civil War reader (and, more so, the modern reader) would consider freedom as some intrinsic quality of humanity in much the same way that it is possible, now, to see the Emancipation Proclamation as an overdue formality — the Civil War itself can be said to have set free people free (like a liberation of civilian hostages in a hostile country who are being held unjustly or against their rights). ...Ultimately, a reader who is upset at the ending is put in a parallel role to Tom — wanting to set a free slave free in a manner that accords to his or her own sense of heroism (and, if you wish, morality). As stated by Fritz Oehschlaeger, "something in us longs for quite a different outcome, one that would allow Jim to retain his heroic stature and force Huck to live up to the decision that accompanies his tearing up of the letter to Miss Watson." [21] In other words, like Tom, the reader wants circumstances to allow Jim and Huck to become heroes according to the reader's definition.

It is not a testament to a fortitude of national character that a significant portion of our population would, in a sense, so dramatically merge the reader's role with that of Tom. To my reading, Twain merely implied the connection, in keeping with his dark, wry humor. Now, in seeking to sanitize the culture that enslaved Jim, making the story more to the tastes of the modern audience, the reader is doing precisely what Tom Sawyer has drawn fire for doing: selfishly making light of the black man's predicament.

January 1, 2011

The Foundation for Everything You Know

It doesn't diminish the fields of history and science to express fascination that it's entirely possible for some bones or fragments thereof to reorder the entire history of man:

A Tel Aviv University team excavating a cave in central Israel said teeth found in the cave are about 400,000 years old and resemble those of other remains of modern man, known scientifically as Homo sapiens, found in Israel. The earliest Homo sapiens remains found until now are half as old. ...The accepted scientific theory is that Homo sapiens originated in Africa and migrated out of the continent. Gopher said if the remains are definitively linked to modern human's ancestors, it could mean that modern man in fact originated in what is now Israel.

The article goes on to note that it could still prove to be the case that the remains are of Neanderthals, not homo sapiens, but the finding still serves as a healthy reminder that relatively little of our knowledge of the past comes from rigorous documentary evidence.

December 4, 2010

Health and Wealth

This is very neat; an animated chart of global health and wealth over two hundred years.

The discouraging aspect is the continued struggle within Africa to advance. On a different note, Hans Rosling breaks some nations into regions to illustrate differences; it'd be interesting to see a similar effort covering the individual states of the U.S.A. over the history of the nation.

October 29, 2010

Dirtiest Campaign Ever? Thus has it always been claimed....

Thanks to the folks at Reason.com for reminding people that political campaigns have been dirty for quite some time (say, a couple hundred years, at least).

April 16, 2010

Paranoia, it's the American Way

As Rich Lowry explains in his latest column, we Americans are perpetually paranoid about our government, whether it's the liberal paranoia throughout the Bush years (Patriot Act, world hegemony) or the right wing paranoia amongst conservatives in the Clinton years (Waco, domestic anti-terrorist laws post-Oklahoma City). Lowry explains that our paranoid view of government has been in our "DNA" since the Founding (and before).

As Bernard Bailyn demonstrates in his classic, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, our forebears prized the thought of the 18th-century “country” opposition in England, which considered the government a clear and present danger to liberty — corrupt, conspiratorial, and insatiable.Lowry's analysis of Bailyn's thesis is spot on and also helps explain why we Americans sometimes tend to buy into conspiracy theories, too. Continue reading "Paranoia, it's the American Way"America’s leaders viewed Revolutionary events through this prism. “They saw about them,” Bailyn writes, “not merely mistaken, or even evil, policies violating the principles upon which freedom rested, but what appeared to be evidence of nothing less than a deliberate assault launched surreptitiously by plotters against liberty, both in England and in America.”

This is the taproot of American paranoia. It’s not in status anxiety, or economic dispossession, or racism: It’s in flat-out distrust of governmental authority. As the Patriot Act shows, in America even the statists can summon a robust fear of government. And would we have it any other way? Would we prefer the natural deference to authority of a Japan, or a political culture as favorable to central government as Russia’s?

March 24, 2010

"Servitude of the regular, quiet, and gentle kind"

In these times, the observations of Alexis de Tocqueville seem as apt as ever:

[Government] takes upon itself alone to secure [the people's] gratifications and to watch over their fate. That power is absolute, minute, regular, provident, and mild. It would be like the authority of a parent if, like that authority, its object was to prepare men for manhood; but it seeks, on the contrary, to keep them in perpetual childhood....For their happiness such a government willingly labors, but it chooses to be the sole agent and the only arbiter of that happiness; it provides for their security, foresees and supplies their necessities, facilitates their pleasures, manages their principal concerns, directs their industry, regulates the descent of property, and subdivides their inheritances: what remains, but to spare them all the care of thinking and all the trouble of living?According to de Tocqueville, it is a misunderstanding of the concept of equality--which rightly understood should be an equality of liberty and opportunity, not of standing--that leads a democratic society down the primrose path to dependency upon government.

[Government] extends its arm over the whole community. It covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd. The will of man is not shattered, but softened, bent, and guided; men are seldom forced by it to act, but they are constantly restrained from acting. Such a power does not destroy, but it prevents existence; it does not tyrannize, but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.Thus, the tropes of democracy are maintained so that "we the people" may elect our own masters.I have always thought that servitude of the regular, quiet, and gentle kind which I have just described might be combined more easily than is commonly believed with some of the outward forms of freedom, and that it might even establish itself under the wing of the sovereignty of the people.

Our contemporaries are constantly excited by two conflicting passions: they want to be led, and they wish to remain free. As they cannot destroy either the one or the other of these contrary propensities, they strive to satisfy them both at once. They devise a sole, tutelary, and all-powerful form of government, but elected by the people. They combine the principle of centralization and that of popular sovereignty; this gives them a respite: they console themselves for being in tutelage by the reflection that they have chosen their own guardians. Every man allows himself to be put in leading-strings, because he sees that it is not a person or a class of persons, but the people at large who hold the end of his chain.By this system the people shake off their state of dependence just long enough to select their master and then relapse into it again. A great many persons at the present day are quite contented with this sort of compromise between administrative despotism and the sovereignty of the people; and they think they have done enough for the protection of individual freedom when they have surrendered it to the power of the nation at large.

ADDENDUM: Michael Ledeen noted basically the same passages a couple days ago, but is optimistic:

Tocqueville had it right, and it’s exactly what has happened on his old continent. Europe has fallen under precisely that sort of tyranny, and our would-be tyrants thought they could do the same here.But the scheme did not succeed, at least the way they planned it. Instead of embracing the tyranny, the American people unexpectedly rose up against it. To use Tocqueville’s metaphor, Americans acted like a recalcitrant child and refused to behave. At which point the tyrannical wannabes decided to slap us down and make us behave properly. They were forced to carry out a coup, a baldfaced seizure of power. Thus, the Demon Pass. Thus the two most memorable lines from the coup plotters: (Pelosi): “we have to pass it to find out what’s in it,” and (Hastings): “there are no rules. This is the U.S. Congress.”

That was not the way it was supposed to happen. We were supposed to go quietly. Instead we fought back, and the final outcome of this big fight–the one I foresaw more than a year ago–is still in doubt. The would-be tyrants may prevail; after all, they have the awesome power of the state. But we have the numbers and a superior vision.

Americans can be very tough in this kind of fight. Ask King George.

March 10, 2010

Hoss Radbourn, The Grays and a Lady

ProJo scribe Ed Achorn just released a new book, Fifty-nine in '84, which tells the story of Charles "Old Hoss" Radbourn's 1884 season with the Providence Grays when he won 59 consecutive games. Old Hoss was indeed a character, something that can be seen even in the stills captured in this video:

But there's more than baseball in the book. Achorn also writes about the history and atmosphere of 1880's Providence and writes extensively about Radbourn's romance and eventual marriage to Carrie Stanhope, "the alluring proprietress of a boarding house with shady overtones, a married lady who was said to know every man in the National League personally."

February 6, 2010

Anti-Dorrite African-Americans in Antebellum Rhode Island

In "Strange Bedfellows", sometime ProJo book reviewer Erik Chaput and Russell J. DeSimone explain how free blacks in antebellum Rhode Island joined forces with the conservative Law and Order party to help put down the egalitarian and populist Dorr Rebellion.

[I]n Rhode Island, forces loyal to Governor King, including some 200 black men from Providence, summarily arrested hundreds of suspected Dorrites. The Law and Order forces, a coalition of Whigs and conservative Democrats, needed all the troops they could get their hands on because many of the state militia units were loyal to Dorr. Black participation in squashing the rebellion made a deep impression on William Brown, the grandson of slaves who had once been owned by the famous merchant turned abolitionist Moses Brown. At numerous points in his memoir, William Brown pointed out that many blacks "turned out in defense" of the newly formed Law and Order party. The "colored people," according to Brown, "organized two companies to assist in carrying out Law and Order in the State." One Dorrite broadside viciously depicted blacks at a table with dogs eating and drinking like barbarians at the conclusion of the rebellion. Indeed, the Law and Order party was frequently referred to as the "nigger party" by the Dorrites.It's a very interesting read and explanation of how politics did, indeed, bring together these strange bedfellows.Ironically, the disenfranchised black allies of the Law and Order party helped to put down a rebellion that claimed to speak on behalf of the disenfranchised. Indeed, the black men who made such an impression on Brown played a key role in suppressing a rebellion that they once had every intention of joining because of its egalitarian ethos. Just as ironically, blacks' support for the Charter government, a relic of Rhode Island's colonial past, helped secure their voting rights when the state approved a new constitution in 1843. The former slave and staunch abolitionist Frederick Douglass maintained in his autobiography that the efforts of black and white abolitionists "during the Dorr excitement did more to abolitionize the state than any previous or subsequent work." One effect of the "labors," according to Douglass, "was to induce the old law and order party, when it set about making its new constitution, to avoid the narrow folly of the Dorrites, and make a constitution which should not abridge any man's rights on account of race or color." This legal triumph, the only instance in antebellum history where blacks regained the franchise after having it revoked, was rooted both in the particular political and economic situations of Providence's black community and in the Revolutionary rhetoric that was part and parcel of Dorr's attempt at extralegal reform.

January 29, 2010

Howard Zinn

It shouldn't go unremarked that radical left historian Howard Zinn has passed away at the age of 87. Zinn, Matt Damon's favorite historian, is best known for his A Peoples History of the United States, a controversial work that has generated mountains of debate within (and outside of) the historical profession. (He even caused a stir around here back in 2004 when he was invited to speak at South Kingstown High unbeknownst to many parents). Disagree with him or not, Zinn will remain hugely influential in the fields of history and political thought for years to come.

Continue reading "Howard Zinn"November 26, 2009

Happy Thanksgiving

To commemorate Thanksgiving this year, I thought it appropriate to post George Washington's original Thanksgiving Proclamation setting aside Thursday, November 26th (exactly 220 years ago!) as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer.

WHEREAS it is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favour; and Whereas both Houfes of Congress have, by their joint committee, requefted me "to recommend to the people of the United States a DAY OF PUBLICK THANSGIVING and PRAYER, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to eftablifh a form of government for their safety and happiness:"

NOW THEREFORE, I do recommend and affign THURSDAY, the TWENTY-SIXTH DAY of NOVEMBER next, to be devoted by the people of thefe States to the fervice of that great and glorious Being who is the beneficent author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be; that we may then all unite in rendering unto Him our fincere and humble thanksfor His kind care and protection of the people of this country previous to their becoming a nation; for the fignal and manifold mercies and the favorable interpofitions of His providence in the courfe and conclufion of the late war; for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty which we have fince enjoyed;-- for the peaceable and rational manner in which we have been enable to eftablish Conftitutions of government for our fafety and happinefs, and particularly the national one now lately instituted;-- for the civil and religious liberty with which we are bleffed, and the means we have of acquiring and diffufing useful knowledge;-- and, in general, for all the great and various favours which He has been pleafed to confer upon us.

And also, that we may then unite in moft humbly offering our prayers and fupplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and befeech Him to pardon our national and other tranfgreffions;-- to enable us all, whether in publick or private ftations, to perform our feveral and relative duties properly and punctually; to render our National Government a bleffing to all the people by conftantly being a Government of wife, juft, and conftitutional laws, difcreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed; to protect and guide all fovereigns and nations (especially fuch as have shewn kindnefs unto us); and to blefs them with good governments, peace, and concord; to promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the increafe of fcience among them and us; and, generally to grant unto all mankind fuch a degree of temporal profperity as he alone knows to be beft.

GIVEN under my hand, at the city of New-York, the third day of October, in the year of our Lord, one thousand feven hundred and eighty-nine.

(signed) G. Washington

August 6, 2009

The Conservatives: Ideas and Personalities Throughout American History

Peter Berkowitz reviews Patrick Allitt's The Conservatives: Ideas and Personalities Throughout American History in the latest Policy Review. Berkowitz explains that Allitt helps explain the "paradoxes that constitute conservatism in America."

The questions that guide his study are straightforward: “Where did conservatism come from, what are its intellectual sources, and why is it internally divided?” In answering them, however, he is obliged to undertake considerable intellectual legwork because a recognized conservative movement in America only came into existence after 1950. This doesn’t prevent Allitt from reconstructing “a strong, complex, and continuing American conservative tradition” stretching from The Federalist to the Federalist Society. It does mean, though, that to justify his decisions about whom and what to include and exclude in the absence of a formal conservative tradition, a common canon, and an established set of spokesmen, Allitt is compelled to spell out the conflicting elements that distinguish a distinctively conservative approach to politics in America.I particularly liked Allitt's definition of American Conservatism (as summarized by Berkowitz):Allitt does not seek to go beyond his role as a historian. Yet his learned and fair-minded reconstruction lends support to the view that the proper way forward for conservatives is neither greater purity nor a more perfect unity, but a richer appreciation of the paradoxes of modern conservatism and a more assiduous cultivation of the moderation that is necessary to hold conservatism’s diverse elements, frequently both complementary and conflicting, in proper balance.

According to Allitt, conservatism is, first, “an attitude to social and political change that looks for support to the ideas, beliefs, and habits of the past and puts more faith in the lessons of history than in the abstractions of political philosophy.” Second, it involves “a suspicion of democracy and equality.” This can be divided into a concern that the formal equality of men before God and law not be confused with equality in all things, particularly virtue, and that too much government power not be placed directly in the people’s hands. Third, conservatism reflects “the view that civilization is fragile and easily disrupted” and therefore it teaches that “the survival of the republic presupposes the virtue of citizens” and calls for “a highly educated elite as guardians of civilization.”

MORE: Tod Lindberg reviewed Allitt's book in the latest addition of National Review and gives Allitt high marks for focusing on conservative history back to the founding and, more importantly, for helping to focus on the central problem of conservatism:

An affection for what’s best in the social order and the urge to protect it are qualities that inevitably lead to a degree of tolerance for the defects of the social order. This is the problem of conservatism, then and now. A conservative sensibility would not necessarily lead to a defense of slavery or toleration of it: See Allitt’s characterization of Lincoln. One might instead note that Calhoun’s racial theorizing was novel and radical more than it was conservative. But a defense in the 1830s or 1850s of slavery as a social institution would necessarily have been conservative.Lindberg hopes Allitt will turn to an examination of Progressivism next: